Pop Quiz:

One of the following tests is reliable but not valid and the other is valid but not reliable. Can you figure out which is which?

- You want to measure student intelligence so you ask students to do as many push-ups as they can every day for a week.

- You want to measure students’ perception of their teacher using a survey but the teacher hands out the evaluations right after she reprimands her class, which she doesn’t normally do.

Continue reading to find out the answer–and why it matters so much.

Validity and Reliability in Education

Schools all over the country are beginning to develop a culture of data, which is the integration of data into the day-to-day operations of a school in order to achieve classroom, school, and district-wide goals. One of the biggest difficulties that comes with this integration is determining what data will provide an accurate reflection of those goals.

Such considerations are particularly important when the goals of the school aren’t put into terms that lend themselves to cut and dry analysis; school goals often describe the improvement of abstract concepts like “school climate.”

Schools interested in establishing a culture of data are advised to come up with a plan before going off to collect it. They need to first determine what their ultimate goal is and what achievement of that goal looks like. An understanding of the definition of success allows the school to ask focused questions to help measure that success, which may be answered with the data.

For example, if a school is interested in increasing literacy, one focused question might ask: which groups of students are consistently scoring lower on standardized English tests? If a school is interested in promoting a strong climate of inclusiveness, a focused question may be: do teachers treat different types of students unequally?

These focused questions are analogous to research questions asked in academic fields such as psychology, economics, and, unsurprisingly, education. However, the question itself does not always indicate which instrument (e.g. a standardized test, student survey, etc.) is optimal.

If the wrong instrument is used, the results can quickly become meaningless or uninterpretable, thereby rendering them inadequate in determining a school’s standing in or progress toward their goals.

Differences Between Validity and Reliability

When creating a question to quantify a goal, or when deciding on a data instrument to secure the results to that question, two concepts are universally agreed upon by researchers to be of pique importance.

These two concepts are called validity and reliability, and they refer to the quality and accuracy of data instruments.

WHAT IS VALIDITY?

The validity of an instrument is the idea that the instrument measures what it intends to measure.

Validity pertains to the connection between the purpose of the research and which data the researcher chooses to quantify that purpose.

For example, imagine a researcher who decides to measure the intelligence of a sample of students. Some measures, like physical strength, possess no natural connection to intelligence. Thus, a test of physical strength, like how many push-ups a student could do, would be an invalid test of intelligence.

WHAT IS RELIABILITY?

Reliability, on the other hand, is not at all concerned with intent, instead asking whether the test used to collect data produces accurate results. In this context, accuracy is defined by consistency (whether the results could be replicated).

The property of ignorance of intent allows an instrument to be simultaneously reliable and invalid.

Returning to the example above, if we measure the number of pushups the same students can do every day for a week (which, it should be noted, is not long enough to significantly increase strength) and each person does approximately the same amount of pushups on each day, the test is reliable. But, clearly, the reliability of these results still does not render the number of pushups per student a valid measure of intelligence.

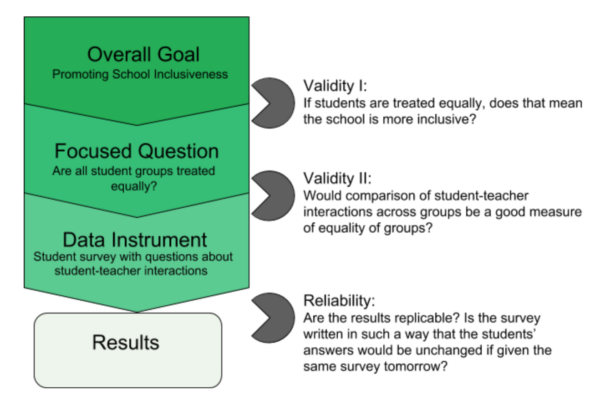

Because reliability does not concern the actual relevance of the data in answering a focused question, validity will generally take precedence over reliability. Moreover, schools will often assess two levels of validity:

- the validity of the research question itself in quantifying the larger, generally more abstract goal

- the validity of the instrument chosen to answer the research question

See the diagram below as an example:

Although reliability may not take center stage, both properties are important when trying to achieve any goal with the help of data. So how can schools implement them? In research, reliability and validity are often computed with statistical programs. However, even for school leaders who may not have the resources to perform proper statistical analysis, an understanding of these concepts will still allow for intuitive examination of how their data instruments hold up, thus affording them the opportunity to formulate better assessments to achieve educational goals. So, let’s dive a little deeper.

A Deeper Look at Validity

The most basic definition of validity is that an instrument is valid if it measures what it intends to measure. It’s easier to understand this definition through looking at examples of invalidity. Colin Foster, an expert in mathematics education at the University of Nottingham, gives the example of a reading test meant to measure literacy that is given in a very small font size. A highly literate student with bad eyesight may fail the test because they can’t physically read the passages supplied. Thus, such a test would not be a valid measure of literacy (though it may be a valid measure of eyesight). Such an example highlights the fact that validity is wholly dependent on the purpose behind a test. More generally, in a study plagued by weak validity, “it would be possible for someone to fail the test situation rather than the intended test subject.” Validity can be divided into several different categories, some of which relate very closely to one another. We will discuss a few of the most relevant categories in the following paragraphs.

Types of Validity

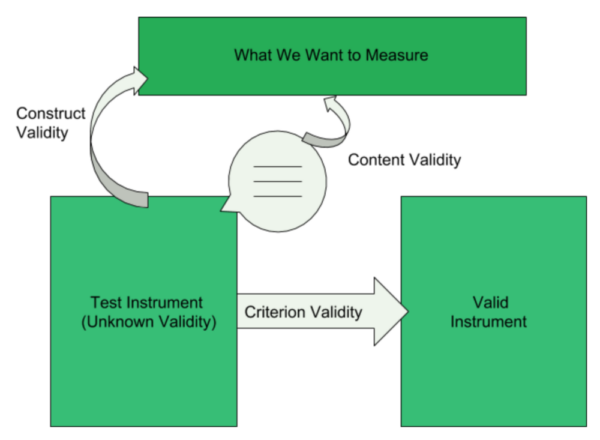

WHAT IS CONSTRUCT VALIDITY?

Construct validity refers to the general idea that the realization of a theory should be aligned with the theory itself. If this sounds like the broader definition of validity, it’s because construct validity is viewed by researchers as “a unifying concept of validity” that encompasses other forms, as opposed to a completely separate type.

It is not always cited in the literature, but, as Drew Westen and Robert Rosenthal write in “Quantifying Construct Validity: Two Simple Measures,” construct validity “is at the heart of any study in which researchers use a measure as an index of a variable that is itself not directly observable.”

The ability to apply concrete measures to abstract concepts is obviously important to researchers who are trying to measure concepts like intelligence or kindness. However, it also applies to schools, whose goals and objectives (and therefore what they intend to measure) are often described using broad terms like “effective leadership” or “challenging instruction.”

Construct validity ensures the interpretability of results, thereby paving the way for effective and efficient data-based decision making by school leaders.

WHAT IS CRITERION VALIDITY?

Criterion validity refers to the correlation between a test and a criterion that is already accepted as a valid measure of the goal or question. If a test is highly correlated with another valid criterion, it is more likely that the test is also valid.

Criterion validity tends to be measured through statistical computations of correlation coefficients, although it’s possible that existing research has already determined the validity of a particular test that schools want to collect data on.

WHAT IS CONTENT VALIDITY?

Content validity refers to the actual content within a test. A test that is valid in content should adequately examine all aspects that define the objective.

Content validity is not a statistical measurement, but rather a qualitative one. For example, a standardized assessment in 9th-grade biology is content-valid if it covers all topics taught in a standard 9th-grade biology course.

Warren Schillingburg, an education specialist and associate superintendent, advises that determination of content-validity “should include several teachers (and content experts when possible) in evaluating how well the test represents the content taught.”

While this advice is certainly helpful for academic tests, content validity is of particular importance when the goal is more abstract, as the components of that goal are more subjective.

School inclusiveness, for example, may not only be defined by the equality of treatment across student groups, but by other factors, such as equal opportunities to participate in extracurricular activities.

Despite its complexity, the qualitative nature of content validity makes it a particularly accessible measure for all school leaders to take into consideration when creating data instruments.

A CASE STUDY ON VALIDITY

To understand the different types of validity and how they interact, consider the example of Baltimore Public Schools trying to measure school climate.

School climate is a broad term, and its intangible nature can make it difficult to determine the validity of tests that attempt to quantify it. Baltimore Public Schools found research from The National Center for School Climate (NCSC) which set out five criterion that contribute to the overall health of a school’s climate. These criteria are safety, teaching and learning, interpersonal relationships, environment, and leadership, which the paper also defines on a practical level.

Because the NCSC’s criterion were generally accepted as valid measures of school climate, Baltimore City Schools sought to find tools that “are aligned with the domains and indicators proposed by the National School Climate Center.” This is essentially asking whether the tools Baltimore City Schools used were criterion-valid measures of school climate.

Baltimore City Schools introduced four data instruments, predominantly surveys, to find valid measures of school climate based on these criterion. They found that “each source addresses different school climate domains with varying emphasis,” implying that the usage of one tool may not yield content-valid results, but that the usage of all four “can be construed as complementary parts of the same larger picture.” Thus, sometimes validity can be achieved by using multiple tools from multiple viewpoints.

A Deeper Look at Reliability

TYPES OF RELIABILITY

The reliability of an assessment refers to the consistency of results. The most basic interpretation generally references something called test-retest reliability, which is characterized by the replicability of results. That is to say, if a group of students takes a test twice, both the results for individual students, as well as the relationship among students’ results, should be similar across tests.

However, there are two other types of reliability: alternate-form and internal consistency. Alternate form is a measurement of how test scores compare across two similar assessments given in a short time frame. Alternate form similarly refers to the consistency of both individual scores and positional relationships. Internal consistency is analogous to content validity and is defined as a measure of how the actual content of an assessment works together to evaluate understanding of a concept.

LIMITATIONS OF RELIABILITY

The three types of reliability work together to produce, according to Schillingburg, “confidence… that the test score earned is a good representation of a child’s actual knowledge of the content.” Reliability is important in the design of assessments because no assessment is truly perfect. A test produces an estimate of a student’s “true” score, or the score the student would receive if given a perfect test; however, due to imperfect design, tests can rarely, if ever, wholly capture that score. Thus, tests should aim to be reliable, or to get as close to that true score as possible.

Imperfect testing is not the only issue with reliability. Reliability is sensitive to the stability of extraneous influences, such as a student’s mood. Extraneous influences could be particularly dangerous in the collection of perceptions data, or data that measures students, teachers, and other members of the community’s perception of the school, which is often used in measurements of school culture and climate.

Uncontrollable changes in external factors could influence how a respondent perceives their environment, making an otherwise reliable instrument seem unreliable. For example, if a student or class is reprimanded the day that they are given a survey to evaluate their teacher, the evaluation of the teacher may be uncharacteristically negative. The same survey given a few days later may not yield the same results. However, most extraneous influences relevant to students tend to occur on an individual level, and therefore are not a major concern in the reliability of data for larger samples.

HOW TO IMPROVE RELIABILITY

On the other hand, extraneous influences relevant to other agents in the classroom could affect the scores of an entire class.

If the grader of an assessment is sensitive to external factors, their given grades may reflect this sensitivity, therefore making the results unreliable. Assessments that go beyond cut-and-dry responses engender a responsibility for the grader to review the consistency of their results.

Some of this variability can be resolved through the use of clear and specific rubrics for grading an assessment. Rubrics limit the ability of any grader to apply normative criteria to their grading, thereby controlling for the influence of grader biases. However, rubrics, like tests, are imperfect tools and care must be taken to ensure reliable results.

How does one ensure reliability? Measuring the reliability of assessments is often done with statistical computations.

The three measurements of reliability discussed above all have associated coefficients that standard statistical packages will calculate. However, schools that don’t have access to such tools shouldn’t simply throw caution to the wind and abandon these concepts when thinking about data.

Schillingburg advises that at the classroom level, educators can maintain reliability by:

- Creating clear instructions for each assignment

- Writing questions that capture the material taught

- Seeking feedback regarding the clarity and thoroughness of the assessment from students and colleagues.

With such care, the average test given in a classroom will be reliable. Moreover, if any errors in reliability arise, Schillingburg assures that class-level decisions made based on unreliable data are generally reversible, e.g. assessments found to be unreliable may be rewritten based on feedback provided.

However, reliability, or the lack thereof, can create problems for larger-scale projects, as the results of these assessments generally form the basis for decisions that could be costly for a school or district to either implement or reverse.

Conclusion

Validity and reliability are meaningful measurements that should be taken into account when attempting to evaluate the status of or progress toward any objective a district, school, or classroom has.

If precise statistical measurements of these properties are not able to be made, educators should attempt to evaluate the validity and reliability of data through intuition, previous research, and collaboration as much as possible.

An understanding of validity and reliability allows educators to make decisions that improve the lives of their students both academically and socially, as these concepts teach educators how to quantify the abstract goals their school or district has set.

To learn more about how Marco Learning can help your school meet its goals, check out our information page here.

Help

Help