Last summer, the major changes for the 2019-2020 school year across AP® courses included a) new unit structures aligned to key course skills, b) teachers gained access to more resources through the launch of AP® Classroom, and c) many exams underwent major changes. All of these changes were meant to better support AP® students and teachers in their preparation for – and success on – the May AP® exams.

Teachers of AP® English Language and Composition and AP® English Literature and Composition experienced one of the most significant changes: the introduction of a new analytic rubric for each exam’s Free Response Questions. This new rubric takes the place of the nine-point holistic rubric that has been in use for 20 years.

P.S. Based on feedback from teachers, the College Board made a few final tweaks to the rubrics, which they released on September 30, 2019. Those changes helped clarify some parts of the rubric. They also released 10 scored student samples for each question of 2018 and 2019 with scoring commentaries!

Using the New AP® English Rubric With Confidence

Such a significant change can be daunting. If you’ve felt less than prepared to use the new rubrics in your class, the good news is there are major benefits with the new approach.

We’ve been trying it out ourselves – scoring hundreds of previously released student samples alongside a team of expert College Board readers – and we believe the new rubric makes it easier to communicate and teach. That’s exciting news for teachers and students.

The analytic style of this rubric offers clearer direct measures of success. In each scoring category, there are technical requirements to meet, which makes expectations clearer for students and evaluation easier for teachers.

Plus, while development and analysis have always been critical to success on AP® English work, this rubric offers a more visible focus on evidence and commentary – as well as clarification of exactly what this means.

“There are two aspects of the new rubric I liked most. The first is the analytical nature of the rubric. Since the categories are broken down into three distinct sections, it is easier to consider each portion of this score separately.

Second, I found the new rubric particularly thorough in its explanation. Each reporting category clarified what types of responses would or would not earn a specific score for that category. The explanations were more focused and clearer for their descriptions.”

— Michael Stracco, AP® English Literature reader

Being big fans of rubrics of all types, but especially analytic rubrics, Marco Learning is here to help. In this post, we break down the big changes and dig into the new rubrics that will be used to evaluate Free Response Questions starting with the May 2020 exams.

Here’s what we will cover in this post:

- Anatomy of the new rubric

- How to use the “decision rules” for scoring

- Implications for teaching

- How to share the new rubric with your students

Anatomy of the New Rubric

While essays were previously graded on a holistic scale of 0 to 9, reflecting overall quality, the College Board has switched to an analytic rubric, which evaluates student success out of 6 possible points across three scoring categories. The three scoring categories are:

- Thesis (1 point possible)

- Evidence and Commentary (4 points possible)

- Sophistication (1 point possible)

Linguistic change! If you’re familiar with the old rubric, you’ll notice a new word choice right away. The new rubric refers to commentary instead of analysis. We perceive this change to be more student friendly, in that it encompasses a broader range of student engagement with the text — rather than simply analyzing the technical aspects of the text/argument, students are encouraged to integrate commentary on important background elements of the text/argument!

Each of these “reporting categories” contains specific requirements that students must meet in order to earn points. The student’s identification and use of evidence continues to be weighted most heavily, with four of the six available points falling within the Evidence and Commentary reporting category.

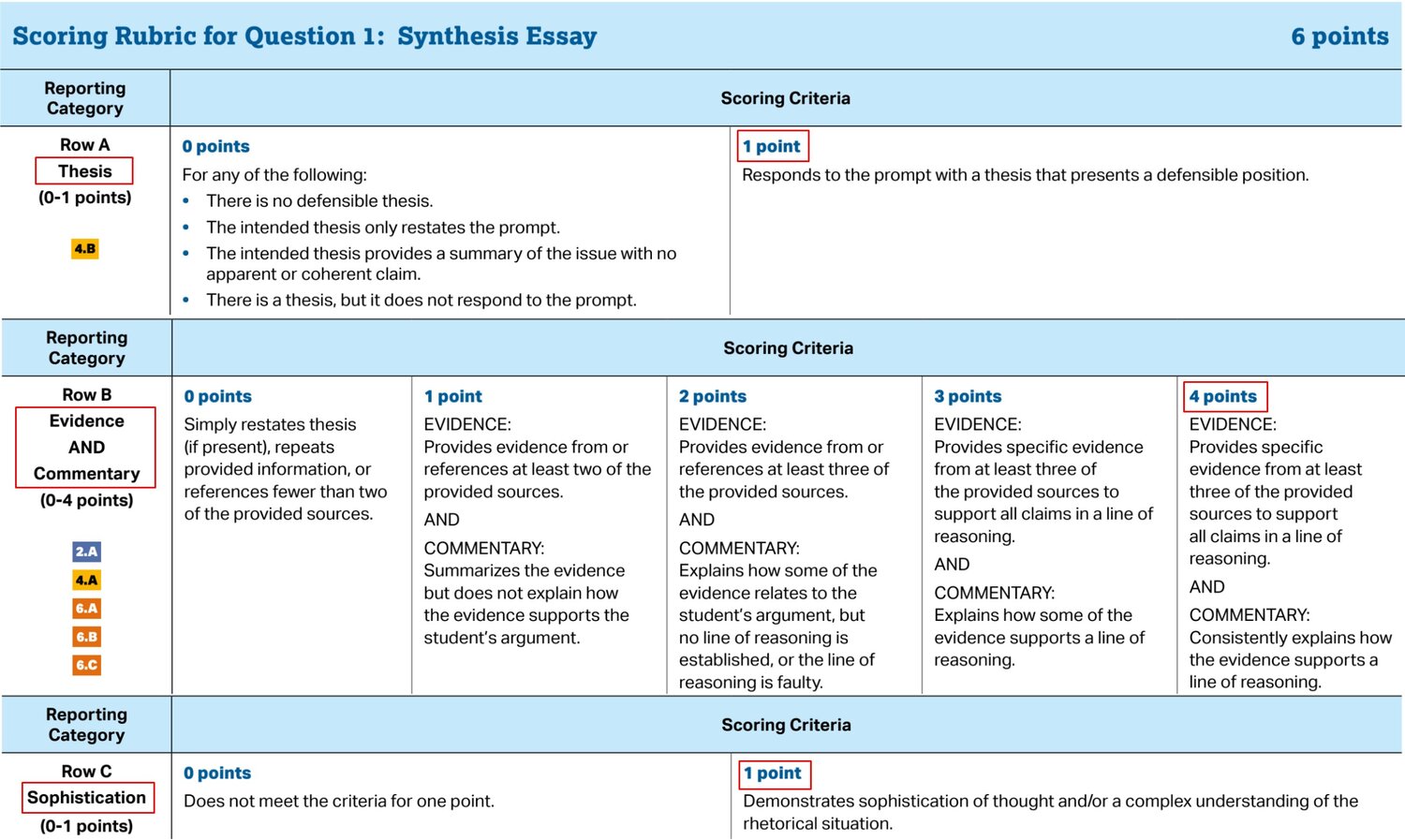

Here are the core elements of the Synthesis Essay in AP® English Language:

How do the rubrics vary by course and/or essay type?

- The scoring criteria for Thesis are nearly identical for all six essay types, with a slight modification for AP® Literature to add that a student’s thesis must “present an interpretation” of the text in question.

- The Evidence and Commentary scoring criteria have slight variations to address the source of evidence that corresponds to each essay type.

- The Sophistication scoring criteria are identical across courses and all essay types.

Decision Rules for Scoring

In addition to the basic rubric scoring criteria, the College Board provides helpful “decision rules” for how to apply the criteria more specifically. Notably, these rules vary by essay type.

Access the complete College Board (and revised) rubrics with the decision rules here:

AP® English Language

AP® English Literature

Applying the Rubric to Student Samples

Many teachers will want to continue to use released exams for student practice (available on the College Board website: AP® English Language, AP® English Literature).

Here’s how to apply the new rubric to your students’ practice timed writings.

A) THESIS

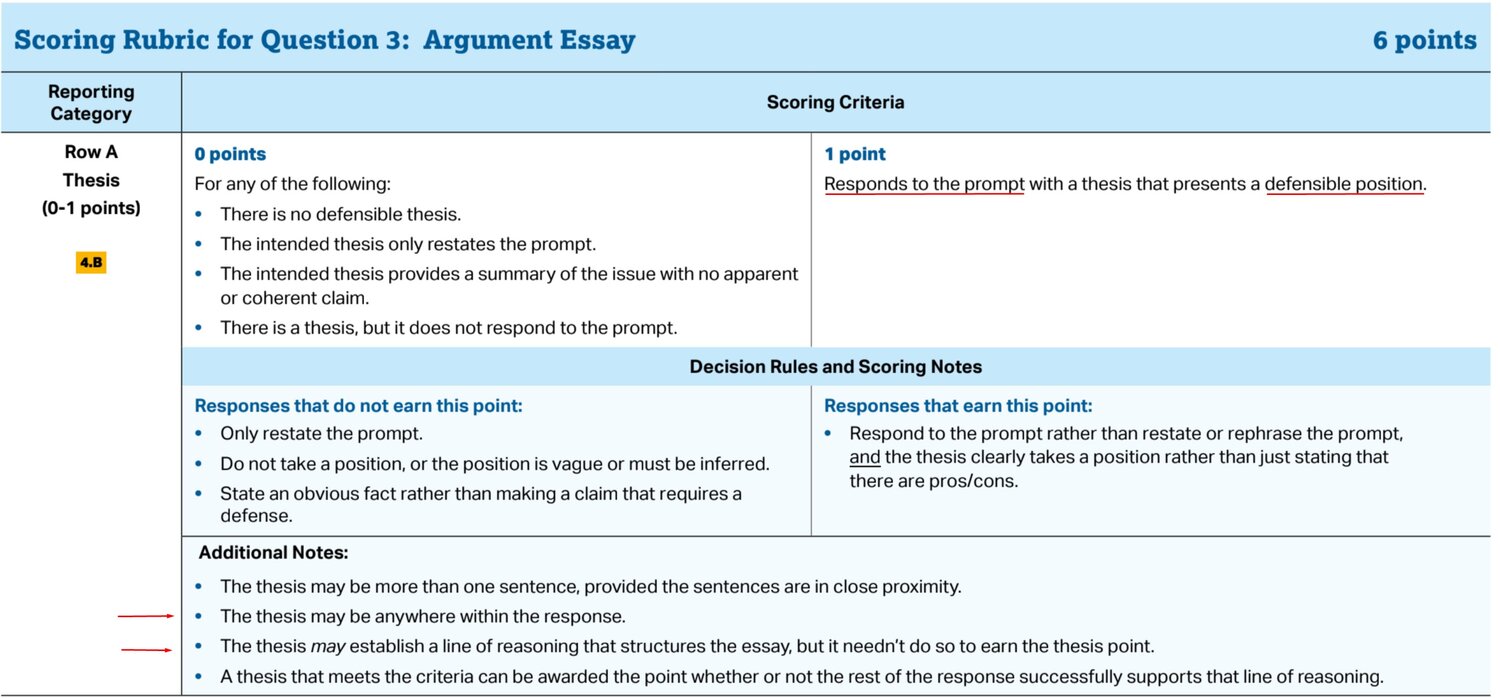

Not only is the thesis a vital part of effective written work, it is now a scoring category for AP® English essays – an explicit requirement. In each essay, students should “respond to the prompt with a thesis that presents a defensible position/interpretation” (the object here varies slightly depending on the question type). Understandably, this must take a position and should go beyond merely restating the prompt or summarizing source texts.

AP® English Language Argument Essay: Thesis Category

Pay special attention to the “additional notes” at the bottom:

First, a thesis located anywhere in the essay may earn the point. While it is typically not good practice for a student to bury their thesis in a conclusion paragraph (because the clarity of their argument may be impacted), a successful concluding thesis would earn the point. When the thesis is not obviously placed in its traditional spot at the end of an introductory paragraph, read closely in case a clear position in response to the prompt is hiding later in the essay.

Second, a thesis may earn a point even if the rest of the response does not support the same line of reasoning. The thesis is evaluated entirely independently from the successful development of the argument.

What changed about THESIS in the revised rubrics?

- Having a defensible position or interpretation (depending on essay type) matters, but the language around “establishing a line of reasoning” has been removed.

- Students are not expected to use the thesis to outline their essay. There have been a few scoring notes added, such as that the thesis does not necessarily need to be a single sentence, but the separate sentences need to be in close proximity.

B) EVIDENCE AND COMMENTARY

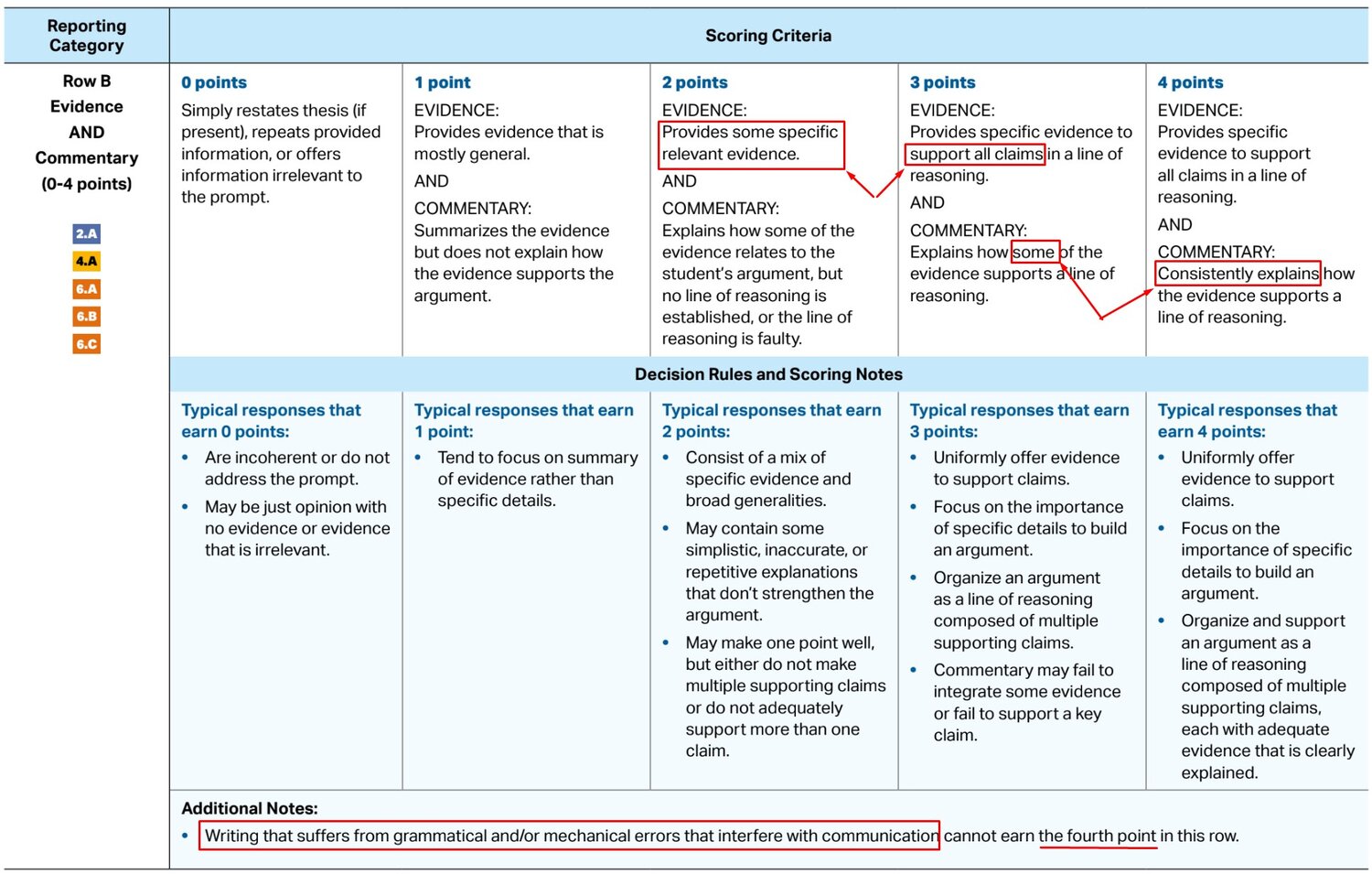

Worth 4 of the possible 6 points, the Evidence and Commentary category carries the weight of the new rubric. While the source of the evidence varies by essay type, regardless of prompt, students are asked to provide evidence for their position and expand on it with commentary that connects the evidence to their position.

Each rubric’s decision rules include descriptions of “typical” responses that fall into each score level. These descriptions will help you decide how to score a response, but may still prove challenging since you’ll still need to determine how successful a student’s explanation is and where that places it on the rubric.

AP® English Language Argument Essay: Evidence and Commentary Category

As our team of AP® readers have practiced applying these rules, we have had the most difficulty determining what meets the level of “explanation” in the expectations of the AP® Language Argument Essay rubric. If a student has provided explanation for their evidence, but not very successfully, for example, they may still be eligible for a score of 3 in this category. This might seem a bit high if you’re oriented to the rigor of the old holistic rubric, but as we’ll explain more below, you’ll need to move away from thinking in terms of the rigor of the old rubric or thinking of essays as “high” or “low.”

If you’re on the fence about a point, we recommend falling back to the classic guidance to reward students for what they do well, particularly in this scoring category. While that specific language has not persisted to this new rubric, based on what we know now, we expect it to persist as a value in College Board scoring on exams.

Note: An essay that does NOT earn the Thesis point is highly unlikely to earn 3 or 4 points in Evidence and Commentary. These higher scores require a clear connection between thesis and evidence.

What changed about EVIDENCE & COMMENTARY in the revised rubrics?

- Compared to the initial version, the College Board made a helpful structural change: Evidence and Commentary are now discussed independently within the scoring criteria.

- There is now more focus on supporting all claims for scores of 3 or 4 rather than simply providing examples or evidence that may not be totally successfully linked back to a claim.

C) SOPHISTICATION

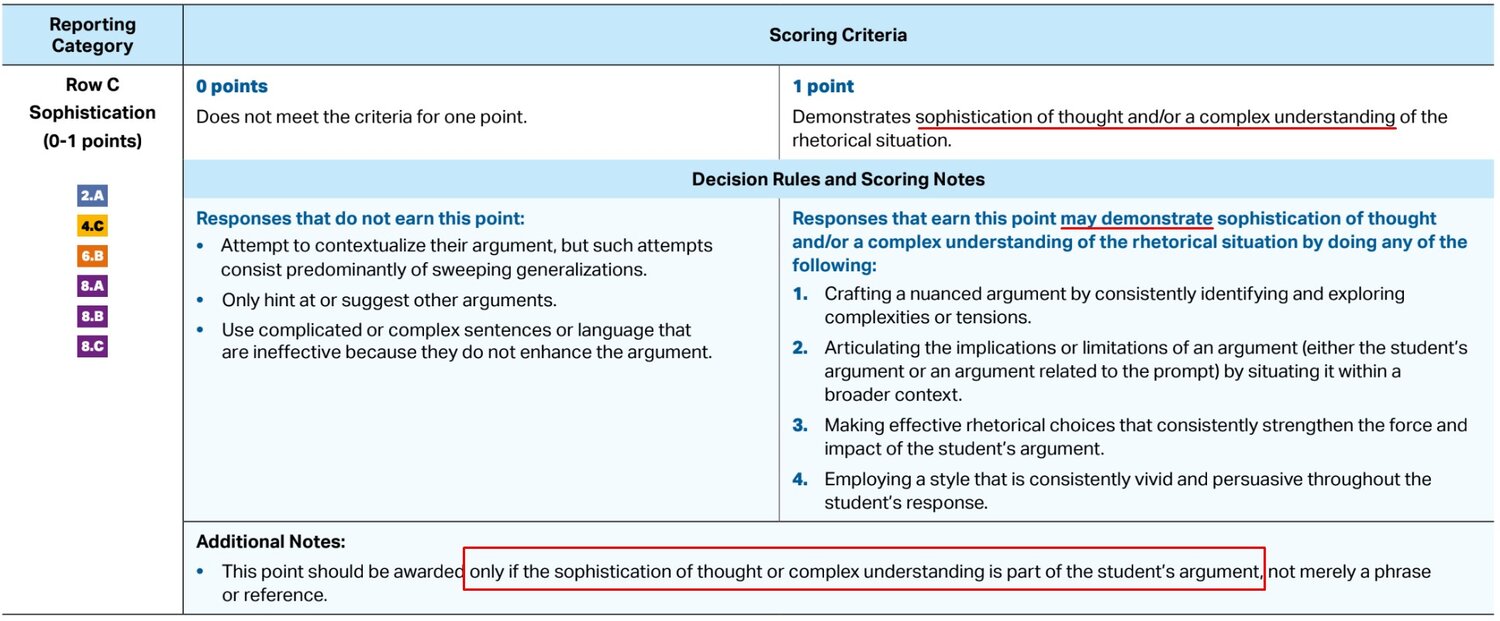

We’ve found the Sophistication component requires the most group norming. There are 3-4 “ways” students might demonstrate sophistication of thought listed in the scoring notes, but the scoring criterion is king: the response must, above all, “demonstrate sophistication of thought and/or a complex understanding of the rhetorical situation.”

As noted in the rubric, sophistication must be part of the argument, not a passing phrase or reference. While it might be easy to coach students to fulfill one or more of the strategies (“check the box”), it will be very difficult for students to successfully earn the point.

What changed about SOPHISTICATION in the revised rubrics?

- The College Board has fine-tuned to the decision rules for this point. It is now more clear that this point is very rigorous.

- There are fewer examples of possible strategies (now 3-4 versus 5-6), notably removing “Utilizing a prose style that is appropriate to the student’s argument”.

Teacher tip: The ways a student might demonstrate sophistication may not be obvious for them to include in a response (e.g., using relevant analogies to help an audience better understand an interpretation or discussing alternative interpretations of a text). While we don’t recommend encouraging your students to incorporate the listed strategies to “check the box,” we do recommend encouraging them to be creative in their engagement with the text. And look to these descriptors for teaching ideas!

Avoid These Common Scoring Mistakes

Make sure your scoring is focused on the core areas of the AP® rubric and doesn’t get caught up by any of these common scoring mistakes.

- Don’t focus on grammar and mechanics. These aspects of writing are relatively unimportant in scoring. However, if grammatical and/or mechanical errors are so frequent and significant that they interfere with your understanding of the essay, the student is ineligible for the fourth point in the Evidence and Commentary reporting category. It is, however, rare to see this level of technical writing errors in a high-scoring essay.

- Don’t penalize for “missing” conclusions. While they do make for “nicer” writing, conclusion paragraphs are usually brief and are not actually required in this exam! A student’s conclusion (or the lack of one) is not weighted in the score.

- Don’t be fooled by flowery writing! Sometimes, a student may write with sophisticated style or flowery language, but fail to adequately analyze evidence or support their argument. While these essays might sound nice, they don’t achieve the main goals of AP® assignments — namely, the development and analysis of evidence in support of a relevant argument. If an essay is written extremely well on the surface, take a moment to consider whether it meets the assignment goals or if sophisticated styling is masking a lack of analysis. Make sure the specific scoring categories guide your evaluation of each student’s essay!

- Be careful not to compare the new analytic scoring with the old holistic scores. If you’re very familiar with the 9-point holistic rubric, you may be tempted to continue to consider essays in terms of their success on the old rubric, but the new analytic rubric requires a shift in thinking. Try not to compare the overall scores of students to each other (an overall score of 3 for two students might reflect success in different scoring categories, for example), and be careful about calibrating to past released student samples that were scored on the old scale.

“I believe that the main challenge with the new rubrics is developing a different mindset from the previous holistic scoring. The one for me that seemed most difficult to discard was seeing an essay as either an upper level or a lower level essay. The new rubric discourages such thinking, which many of us experienced scorers often relied upon when first reading through an essay.”

— Michael Stracco, AP® English Literature reader

Implications for Teaching

We asked Michael Stracco, a long-time English teacher with sixteen years experience as a College Board reader for the AP® Literature and Composition course, for his advice for teachers when guiding students on the new rubric.

What advice would you give to teachers when guiding students on the new rubric?

Any rubric is going to be a bit formulaic when it comes to preparing students. To the degree that the rubric describes good writing, this new rubric is clearly good teaching of writing. For example, the descriptors of a good thesis sentence are excellent. A teacher would do well to teach a student how to write a good, clear thesis which answers a prompt. However, in years past, it was conceivable that a thesis could be implied on these essays since a stated thesis was not a part of the rubric. Now it is a part of the rubric. Because of this change, all students must now be certain to have a clearly stated thesis. This is a bit formulaic, but it is what teachers must teach in order to prepare their students well for the test.

So this would be my advice to teachers:

- Remember that you are always a writing teacher. The aspects of writing a literary analysis response are still just teaching how to write well. To be specific, teach students to rely upon the text, to make an analysis of the text, and to elaborate upon that analysis. Be certain to teach students the difference between summary and analysis. This is the heart of scoring well in Row B.

- I would teach students to put the thesis in the introduction and to underline It always helps for a writer to think about audience in all writing, and in this case the audience is someone who is reading many essays and needs to be certain to see the thesis to assign the point.

- Regarding a thesis: Teach students that creating a good thesis has two purposes. The first is so that the reader knows where the piece is headed. But the second is so that the writer knows where the piece is headed.

- Related to this: Planning is essential before writing. You need to know your thesis so that you can keep the piece focused. As an experienced reader, I sometimes would see a student write him/herself into a good essay. The piece would develop into a better essay than the thesis. With a full point being for a good thesis, a student must plan before writing and must write within the context of the thesis or no point would be assigned.

Next Steps for Tackling the New Rubric

As you begin to use the new AP® English rubrics in your classroom this school year, we encourage you to use the rubric categories and language to guide the skills you teach and follow these next steps:

- First, download our fillable Teacher English Language Scoring Rubric to keep track of all of these pointers when you are evaluating student work on the new AP® English rubric. Make copies to reuse with each essay you grade!

- Second, plan a lesson to introduce your students to the new rubric. Review the rubric with them and prep them to use it for self-assessment on their next essay.

- Third, assign your first practice essay of the school year with confidence! Plan to have your class practice writing thesis statements, and give students plenty of opportunities to practice and workshop more straightforward evidence and commentary strategies.

If your school partners with Marco Learning, take advantage of the opportunity to get personalized feedback for your students from one of our qualified Graders. Graders complete qualification modules to demonstrate proficiency with the new rubric in addition to calibration exercises specific to each prompt.

Log in to your Marco Learning account, and pick from any College Board released prompts dating back to 1999. Scoring and feedback on all AP® English prompts will be completed using the new rubrics so students and teachers can be prepared for the exams in May!

If we don’t currently work with your school, learn more about how Marco Learning supports AP teachers here.

Help

Help