In many classes, the announcement that it’s time for peer review brings a smile to the teacher’s face but groans across the classroom.

Having students comment on each other’s essays might seem like a fun, effective activity with straightforward benefits, but the negative association that many students have with peer review reveals that the process is often run ineffectively.

In order for students to learn how to respond thoughtfully and constructively to their peers’ work, teachers must make a number of careful choices about what peer review will look like and avoid common pitfalls that hamper the process.

Why Peer Review is Important in Writing

If peer review is so difficult to manage effectively, why bother? There are a number of unique benefits for both teachers and students.

BENEFITS OF PEER REVIEW FOR INSTRUCTORS

As the UC Denver Writing Center explains, advantages of peer review for the instructor include a reduced workload (yes, please!), more opportunities for introverted students to earn participation points, and stronger papers to grade since students are encouraged to think through areas of confusion before the paper is due.

BENEFITS OF PEER REVIEW FOR STUDENTS

Peer review has the potential to help students as well; in particular, it can help students think about texts more critically.

This is a skill that will help them identify strengths and weaknesses in their own writing as well as approach other course readings with a more advanced academic mindset.

These gains are particularly important because recent analyses show that U.S colleges are “falling short when it comes to teaching students critical-thinking skills such as making cohesive arguments, assessing evidence and interpreting data.”

Source: http://gse.harvard.edu

Peer review can also help students think beyond themselves during the writing process.

Students often begin by not considering audience at all while writing, but peer review encourages them to consider a specific reader (e.g. the teacher or peer reviewer), which can ultimately lead them to write for a broader academic audience.

The ability to enter into an existing academic conversation is a vital skill for college writers. Beginning to develop it in middle and high school can help prepare students for college writing and beyond.

The potential benefits of peer review for students are also supported by the current research on teaching and learning.

The Education Endowment Foundation’s summary of the most beneficial practices for teaching includes “feedback, peer tutoring, collaborative teaching, metacognition, and self-regulation—all components of effective peer review.”

Specific studies have shown quantifiable academic improvement as a result of peer review. One 2016 study that focused on EFL students found that, according to pre- and post-essay test scores, “peer reviews contributed to an improvement in student writing abilities, which included improvements that were retained after the peer review practice ended.”

PEER REVIEW, THEN, IS A HELPFUL TOOL THAT HAS THE POTENTIAL TO IMPROVE NOT JUST THE WRITING BUT THE WRITERS THEMSELVES.

The Basics of Peer Review

One of the best ways to increase the chances that peer review will be successful in your classroom is to thoughtfully and intentionally plan many aspects of peer review in advance.

According to the WashU Writing Center, peer review works best:

- With papers that are five pages or less

- After a complete draft but while there is still substantial time for revision

- When the first session is early in the year

- When the first session focuses on a shorter piece of writing (1-2 paragraphs)

- When reviewers are given specific tasks to complete (ex: “rephrase the thesis”)

While these are good basic guidelines, there are still important (and even controversial) decisions to make about the nature of your peer review.

For example, depending on the size and dynamic of your class, you’ll need to decide whether students should work in pairs or groups to do peer review. In conjunction with that, it’s important to decide whether the pairs or groups will rotate—both within a specific peer review session and over the course of the year.

There is currently no research consensus on the most effective way to run peer review, so you will have to decide what works best for your specific class.

BENEFITS OF PEER REVIEW IN GROUPS

The UC Denver Writing Center recommends putting students in groups of five and keeping them the same for the entire semester. It’s easy to see how the static setup could lead to greater trust among students as the months progress and the larger group could benefit students by giving them a broader set of responses to their work.

Mr. Olio, a high school English teacher featured by the Teaching Channel, prefers to put students in groups as well, calling them “critical friends groups” rather than “peer review groups” to emphasize the ongoing relationships among peer reviewers.

If you decide to assign larger groups, it is even more important to have an established peer review protocol for students to follow in order to avoid chaos.

One NCTE guide to peer review recommends that you have students read their peers’ papers before coming to class to speed up the process while working in groups. In his class’s peer review process, Mr. Olio tells his high school students to start with their “warm and fuzzies” about each paper and then move to “cooler feedback” and later invite the writer back in for clarifying questions.

Writer silence until the end of the discussion is an important part of Mr. Olio’s protocol. He believes that asking writers to simply absorb the discussion until the designated question time at the end “forces students into an understanding that their text is indeed a text”– they won’t be able to stand over readers’ shoulders and defend it in real life.

Whatever your protocol looks like, writing it up on the board every time your students do peer review (and referring to it often) will be a good start to an organized process for group peer review.

BENEFITS OF PEER REVIEW IN PAIRS

Despite the advantages of small group revision, some teachers believe that paired peer review is more helpful for their students.

Paired review is more intimate, which can allow writers and readers to be more vulnerable about their questions and concerns, and some teachers believe that having students look at fewer papers increases “the likelihood that each paper receive[s] a quality response from at least one editor.”

As with group peer review, it is important to establish a routine for paired review, though this can look different. For example, in paired review, it is more possible to read papers aloud, which can be a valuable tool for writers to spot everything from typos to lack of transitions in their own writing.

One writing professor has their students start every peer review session with two printed papers: one for their reviewer and the other for themselves.

As the writer reads the paper aloud to their reviewer, the writer marks issues and areas to come back to on their copy of the essay. Afterward, the partners fill out a checklist and discuss suggestions for revision together.

This professor then has students switch partners, which happens at least once for each essay. This way, “students could compare reviewers’ responses and decide whose advice would be the best to follow.”

In addition, “if both reviewers pointed out the same errors or suggested a different way to approach a topic, the student could be reasonably assured that they needed to heed the advice.”

Another professor just has students partner up once per paper but makes sure that students have different partners for each paper across the semester, totaling at least three partners per semester. This way, students have the chance to interact with different kinds of writers and different kinds of papers—all with the knowledge that if this match isn’t ideal, it’s also not permanent.

How to Give Peer Feedback on Writing

Even more important than the number of people with which students will discuss their papers is the content of their discussion. As the facilitator of peer review, it’s important for you to narrow the range of their discussion.

GRAMMAR

For example, many guides to peer review recommend that teachers discourage editing and extensive discussion of grammar.

The UC Denver Writing Center explains that “grammar instruction is not generally appropriate for a rough draft” since “students are unable to transfer grammatical feedback to other writing” and “edits will probably be lost during the revision process.”

In the same vein, one teacher reminds students before peer review that “it’s a waste of time to polish a sentence that you later decide you don’t need.”

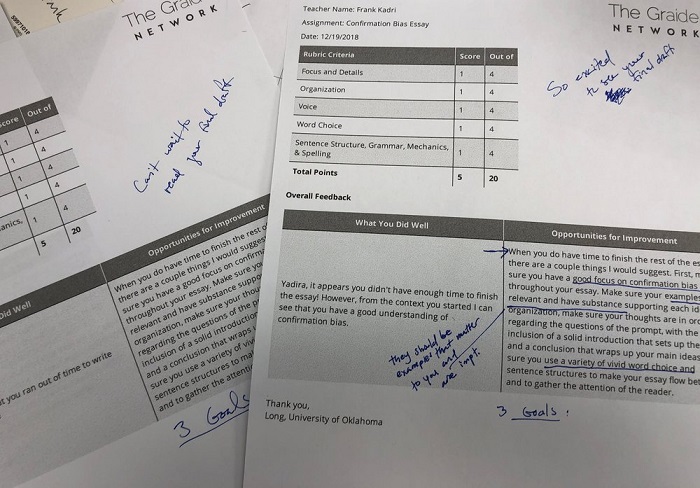

Marco Learning gives our virtual grading assistants similar advice, and if you use our paper grading service for teachers, you’ll notice that our trained graders tend to prioritize higher order concerns such as argument, evidence, and organization when providing feedback to students (unless a teacher specifically directs graders toward sentence-level concerns).

EVALUATOR VS. READER

However, while many instructors are in agreement about focusing on argumentative aspects of papers, a more controversial topic is whether students should give responses as an evaluator or stick to responding as a reader.

One professor feels strongly that providing “clear actions and suggestions” is the most helpful way for students to respond to writing as it is a “form of peer teaching, a powerful learning strategy for the reviewer.” Accordingly, some teachers will give reviewers the same rubric that they will use to grade the paper rather than a peer review checklist.

That said, many other teachers feel that students are “not necessarily… qualified to apply these criteria effectively, and they may feel uncomfortable if they are given the responsibility to pronounce an overall judgment on their peers’ work.”

Instead, the director of the University of Minnesota Center for Writing actually forbids the use of the word “should” and instead asks students to “phrase their responses in ‘I’ language (‘I hear…,’ ‘I’m confused when….,’ ‘I’d like to hear more about…’” In this model, the reviewer is not an uncomfortable surrogate for the teacher at all but rather a mirror for the reader to see their own ideas reflected back to them.

There is, of course, a third way as well, where students are not “outlawed” from giving suggestions when necessary but are generally encouraged to provide comments about their experience as a reader.

Regardless of what you end up choosing—grammar or no grammar, reader or evaluator—it is important to set your preferences as clear guidelines for your students before they embark on their first peer review session.

Looking Forward

Integrating a successful peer review framework in your classroom takes time and planning, but the benefits speak for themselves. As an educator, building peer review into your writing process will allow you to spend less time grading and more time on the other important instructional tasks you love like designing innovative lesson plans and working with students one-on-one. Peer review will also allow your students to build critical thinking and analysis skills, while growing and developing as writers.

Looking for more information on this topic? Check out Marco Learning’s How to Make Peer Review Successful – Part 2.

Help

Help