Data has risen to be the defining theme of the last decade, as both individuals and companies alike have found ways to use data to improve their businesses and lives. School leaders are no exception. For decades schools only collected data on national achievement tests, but school leaders are now attempting to expand these horizons; many schools are establishing a culture of data that may be used to guide the decision-making of school leaders and further individualize the experiences of students.

What is a Culture of Data?

A culture of data involves harnessing facts and statistics to improve the day-to-day operations of a school. Within a developed culture of data, superintendents use data to inform progress toward the vision they have for students. Principals use data to understand their students and staff and identify what support their school needs in order to achieve the district’s vision. Teachers use data to identify what these needs are, create and adjust curriculum, reach out to students in need, and individualize the learning experience. The Educational Leadership magazine expands on this idea, stating that, “In a data-driven culture, there is an institutionalized willingness to use numbers systematically to reveal important patterns and to answer focused questions about policy, methods, and outcomes.” Data should not only be used to measure student success but also to guide decision-making on a student-, class- and school-wide basis. Essentially, data needs to have a purpose.

This purpose often begins with a question, which will then determine the data that school leaders collect. For example, a broad question about the general success of the school could be measured with standardized or state test scores. Standardized test data could indicate large areas for improvement. But, a culture of data can (and should) be even more illuminating. The ability to collect various forms of data allows schools to break down vague goals into specific educational objectives. Principals can then use these objectives to ask focused questions and collect the data to answer them.

The American Association of School Administrators (AASA) writes that schools with established cultures of data are able to answer not only “how well students are performing on tests” but they can also determine “which students are not doing well and why, and then [seek] improvements.” AASA gives the example of a school district in California which, on the whole, was performing quite well at the 80th percentile in norm-referenced tests. But, upon a closer examination of the data, they found pockets of students performing at the 30th and 40th percentiles. Analyzing the data allowed the district to identify common traits among these students and craft targeted solutions for them. The ability to narrow areas for improvement allows for the individualization of the learning experience and targeted solutions, thus paving the way for data-based decision making.

The Benefits of Data-Based Decision Making

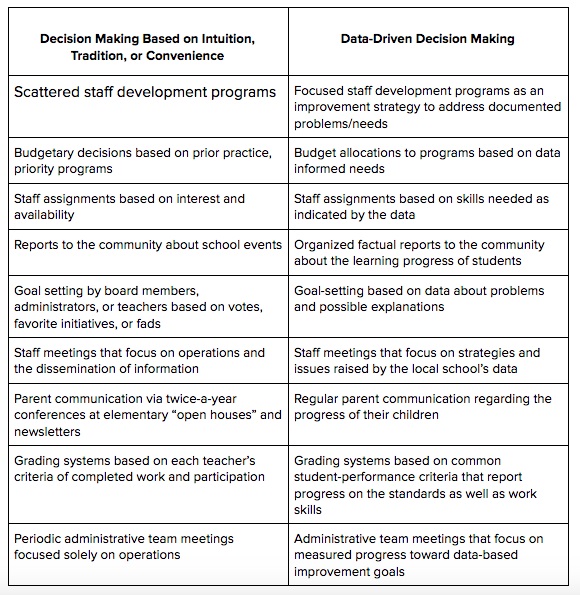

Indeed, data-based decision making is simply informed decision-making, which often, according to the AASA, “takes the emotion and rancor out of what can be tough calls” for school leaders. For example, principals, upon seeing in the data that iPads were not effective in increasing writing fluency, may decide to no longer allocate funds to them. When schools establish a culture of data, data is at the center of virtually all decisions the school makes: decisions about budgets, staff, goals, and more. To understand the transition into data-based decision making and why it’s useful, see the chart below, reproduced from Learning Point Associates, a nonprofit educational consulting organization.

We would also add to this list that a culture of data allows schools to understand and change, if necessary, the culture and climate of the school as a whole. Schools can use perceptions data, or data about how students, teachers, parents, or other members of the community perceive the school and its culture, to understand their role in the community and how to improve it. For example, the Milwaukee public school district offers a survey for students and staff to talk about the culture and climate of the school, “in an effort to provide data to schools that inform their plans in creating school climates that feel safe and welcoming to students, families, and staff.” This district found research indicating that development in areas of “effective leadership, involved families, supportive environment, collaborative teachers, and ambitious instruction” will improve schools and narrow the achievement gap. Upon setting this goal, they decided that the best way to measure those criteria would be through a survey at each school. Without a culture of data, it would have been much more difficult to find out the information needed to make a positive change.

Using Data to Individualize Learning

Much of the literature, including the list above, focus on school- and district-level initiatives. But in order to achieve lasting improvements, a culture of data must also be established at the classroom level. Teachers who are already short on time and resources may not have the bandwidth to collect data on their students, much less analyze it. Marco Learning seeks to change this. By shifting the burden of grading from teachers to trained aspiring teachers (aka Graders), Marco Learning frees up time for teachers so that they can focus on analyzing grades and forming plans around identified areas for improvement.

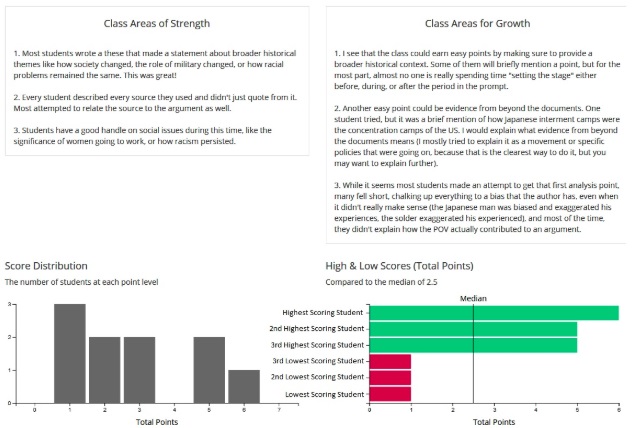

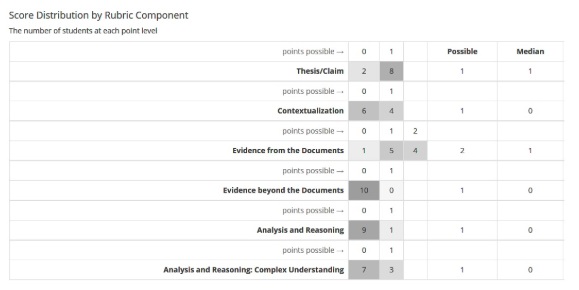

However, broad quantitative data, such as essay scores at the class-level, are limited in their usefulness; this information is a start, but it still doesn’t explain why the scores are what they are. Marco Learning attempts to solve this problem by translating the culture of data into qualitative feedback, going beyond the numbers to identify what is going on in relevant terms. When a Grader completes an assignment, they provide each student with both a score and written responses about what the student did well and what still needs work. Upon finishing all the papers, the Grader reflects on problems that persisted among students as well as topics that the class has clearly mastered, and they write a class summary accordingly. The teacher then receives the individual reports, the class summary, and a sheet with summary statistics including the mean, median, minimum total score, and maximum total score. Below is an example of a score report from an AP US History essay assignment.

These statistics help the teacher to easily identify general areas for improvement, while the summaries explain what specific problems students struggle with in these areas. In a high school English class, students may struggle with smoothly integrating quotes in a literary analysis essay, but they may have mastered writing theses. In a math class, students may have no problem simplifying an algebraic equation but can’t quite grasp how to determine the shape of the graph. The class summary enables teachers to understand these needs without having to look through every paper, thereby allowing them to immediately allocate their time to solving these problems.

Marco Learning also supports teachers in developing solutions unique to different classes and different students. Grading is done by period, so if a teacher submits essays based on the same prompt for 3 periods, they will receive 3 separate score reports, one for each class. Then, teachers can easily see the differences between their classes: is first period struggling with a concept that third period has already mastered? Are all class periods struggling with the same concept? Armed with that knowledge, a teacher may reformulate their lesson plan to review a concept that the data shows students need some extra time with. They also easily see which students need extra support and can find a way to best reach out to them.

A Better Way to Measure Progress

The culture of data extended to the classroom easily allows for teachers and schools to keep track of students over time. Data that keeps track of the same individual over different periods is called longitudinal data, and it is famously helpful in measuring the effectiveness of initiatives. According to the AASA, “Longitudinal measurement — conducted consistently from year to year — is necessary to properly measure progress, growth, and change. The consistency of the data elements — necessary for any long-term data collection and analysis — reduces confusion.” In simpler terms, following the same individuals over a prolonged period of time controls for variations among individual characteristics, such as personality traits. For example, suppose a principal wants to measure the success of a reading program. Looking at standardized reading test scores of groups that participated in the program in different years, the principal is unsure if differences in results stem from differences between the groups or the program’s impact. This principle would only be able to isolate the effects of the program itself by following the same group of students from before the program until after its completion.

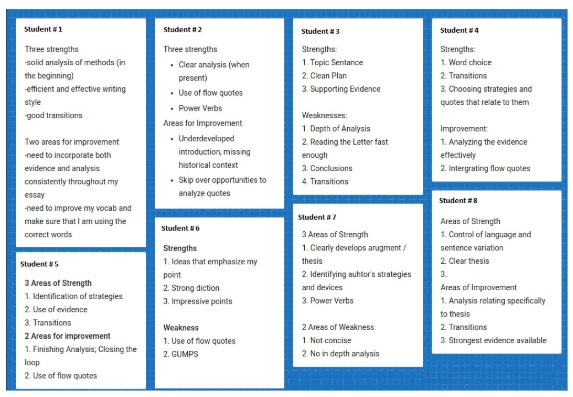

However, in spite of its advantages, longitudinal data is notoriously difficult to obtain and analyze. Marco Learning seeks to solve this problem by making longitudinal data accessible to teachers at the classroom level. For example, one particularly crafty teacher took advantage of Marco Learning’s qualitative feedback to keep track of his students’ progress throughout the school year. After receiving feedback on an essay, his students summarized their strengths and weaknesses into bullet points (see the picture below). The teacher aggregated this data and submitted it as a supporting document alongside the next assignment. This report allowed Graders to focus their comments, explaining to the student how to improve persisting weaknesses, congratulating them on weaknesses that had turned into strengths, and encouraging those who had mastered their weaknesses to tackle new areas of growth. The teacher was then able to track his students’ growth. As an added benefit, putting this data in the students’ hands gave them a better understanding of their own writing, providing them with the agency in their own education– an important outcome that is often forgotten in discussions about cultures of data.

So, how do school leaders start to develop this culture of data? After a review of district and school goals, school leaders should create questions about what achieving those goals would really look like. Then, leaders should think about what data would answer those questions, and how to get it. While some larger school districts have entire departments dedicated to research and data analysis, not every solution needs to be complicated. Perceptions data can easily be collected by having teachers pass out surveys in each class. For performance data, the data collected will depend highly on the goals of the district. No matter what the goal is, developing a culture of data will allow schools to improve the experiences of both students and staff by individualizing the learning experience, allowing for a deeper understanding of school culture, and providing a basis for better decision-making.

If you’re interested in how Marco Learning can contribute to your school’s culture of data, contact us.

Help

Help