Math and reading response-to-intervention get a lot of attention. School leaders discuss them regularly, and most schools have programs and assessments focused on them. Hours are spent doing text-based planning, giving common assessments, and constructing text-dependent questions for reading instruction.

But what about writing? If we are being honest with ourselves, it receives far less recognition, even though it is directly linked to accelerating reading skills. D’On Jones, Reutzel, and Fargo (2010) found that strategic writing models impacted reading outcomes as early as kindergarten. Purposeful and systematic instruction in writing is necessary not only to develop students’ ability to grow as great writers but also to grow across multiple subject areas.

In order to explore RtI considerations for writing, we must first look at components of Tier I (all students in all classrooms) to determine the effectiveness of current writing instruction. After analyzing that data, we will then think through foundations of writing instruction.

As Tier I effectiveness increases, school leaders must also implement standards and skills-based intervention in Tier II, which we will cover next. Our last topic in this post will be how leaders can support intensive intervention through methodical programs and structures in Tier III.

All of these tiers require a foundation of strong data. Below are some data-related terms to reference as we move forward in discussing each of the tiers. Valid and reliable data originates in implementing the following best practices:

- Universal Screener: An adaptive, grade level diagnostic assessment to identify the specific level and gaps of all students

- Program Diagnostic: Tier II and III programs often have a mini-diagnostic assessment to help determine starting concepts and skills for intervention services

- Progress Monitoring: A targeted formative assessment given to students on a single skill or learning goal in intervention to determine if student is responding to intervention

- Benchmarking: Administering the Universal Screener in Winter and Spring to determine if the gap is closing and to identify at-risk students

About This Series

At the end of the series, you will be able to answer the following big questions:

- What are the basics of Response to Intervention (RtI)?

- How do Response to Intervention and writing live together in my school?

- What do I need to implement a high-quality Writing RtI?

If you missed the first part of our series, Response to Intervention: A Primer, you may find it helpful to hop backwards to get caught up on the basics. However, if you’re in the trenches and use acronyms like CBM, EIS, and SLD all day, it’s best to continue on here!

Tier I: Practices Across the Building

To ensure that every student succeeds in writing, the more intense tiers of the program must be put aside to first dive into the culture and practices of writing in the school. Recalling the RtI triangle in our first blog post, 80% of students must be at or above grade level. To start, begin with writing practices that 100% of students receive in all classes. A quick warning about considering writing in your school: too often, leaders focus on just English or ELA classrooms. The culture and practice of writing extends to the culture, models, and strategies in place throughout the entire building in all subjects.

A NOTE ON WRITING CULTURE

As a leader, there are plenty of methods that you could use to determine the culture of writing in your school. Here are some that research suggests (and that I’ve personally tried!):

- Sit in on writing tasks in several different courses with several different teachers. Complete the lesson with the students.

- Create digital or manila folders for two groupings: Vertical-Subject and Horizontal-Grade. Grab student binders or go through their Google Drive to collect completed writings. Assemble the folders to see the prescribed tasks, the expectations for writing, and what students actually did in response. Tip: Don’t tell anyone ahead of time that you are doing this so that you get an accurate picture.

- Create and distribute “a culture of writing” survey for teachers, students, and parents to complete. How do students feel about writing in your school? How much time is spent writing at school? How much time do they spend writing at home? How do teachers approach planning for differentiated writing tasks? Are writing tasks only standardized test related?

- Create a focus group of educators and/or students to determine the effectiveness of feedback on the writing process. How often do students edit and revise their writing? Do they receive high-quality feedback from teachers, peers, and outside sources (like normed and trained Graders)? Is the feedback perceived to be helpful and to advance craft, structure, and content?

Walking through the halls of the various schools that I advised, I often got two types of responses. Students either thought writing was done to get a good grade or students saw writing as a way to express ideas. In my experience in education, this idea is at the heart of culture.

Is writing something that I am made to do in order to get class credits or a passing grade? Is writing something I do to express my ideas, opinions, and analysis?

Other elements stem from these questions when it comes to culture. If the culture of a school and its classrooms empower writing than it is more likely that 80% of students will reach at or above grade level mastery.

ROUTINIZED TIER I PRACTICES

As you determine culture within Tier I, it is also important to dig into the models used in the school or district. Educational institutions usually have one of two stances when it comes to writing in their school: Either every teacher has individual ownership of writing in their room or the organization provides a model to follow.

Early in my career, each teacher designed their own acronym for well-written paragraphs and instituted their own form of peer revision. Later in my career, I started leading by instituting the Writer’s Workshop model across all courses in all grades. There are costs and benefits to each path, but I want to point out that there is often more acceleration when students experience an aligned and familiar instructional model.

Take a moment right now and think: Which way does your school approach writing models? If every teacher has ownership, it might be relevant to calculate how many different structures and models are used by teachers in total. To approach this from a student’s perspective, consider how many different ways they hear about what good paragraph organization is in writing. How powerful would it be to have an aligned message across all classrooms?

A student goes to social studies to compose a review of published literature and hears the same acronyms as in science. During the next block, the student heads to foreign language, seeing the same posters they saw in the previous four classrooms describing the writing process. Acceleration is amplified through aligned integration of schoolwide structures.

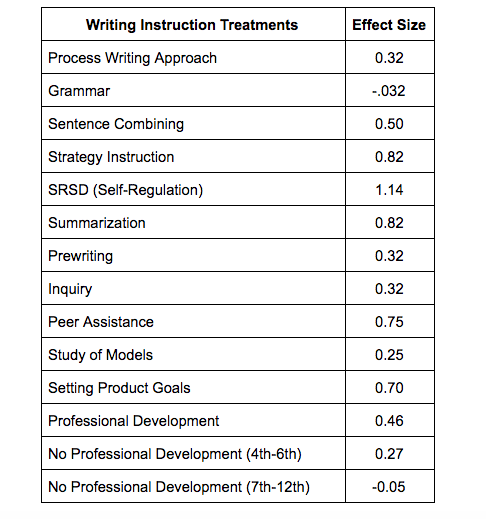

Keeping that in mind, let’s take a look at some best practices for writing instruction and programs according to peer-reviewed research:

For explanations of each model, check out this report: WritingNext.

If you’re unfamiliar with effect sizes in research, check out Dr. Chris Balow’s article “The ‘Effect Size’ in Educational Research: What is it & How to Use it?”.

While looking at this list of best practices and their impact on student outcomes, reflect on the routinized practices in place at your school. What happens day in and day out in every classroom across the school? Think about what is on the walls of every room. Think about what behaviors and patterns happen every time students write.

Whether all classrooms use model studies or peer assistance, summarization or setting goals, the model that is most implemented becomes your Tier I program. If your implemented model is highly-effective and done with fidelity, then roughly 80% of students should score at or above grade level on a nationally normed and standardized assessment.

That becomes the first step in RtI: ensuring that schoolwide Tier I programs are effective enough to grow and intervene within all classrooms to reach the 80% mark.

TIER I INTERVENTIONS

RtI requires intervention in the general classroom. This is nothing new; in fact, it has long been a part of good teaching.

Typically, for a writing task, the educator compiles a list of common misunderstandings, misconceptions, or skill gaps that the class has. Usually this is done while the students are writing the first draft or after it is turned in. The educator then separates and intervenes in small groups based on the issue at hand.

Some educators also provide individual feedback on first drafts for students to correct and develop further. Students then grow from this intervention and thus the entire school is at 80% for Tier I.

This sounds nice in theory, but time becomes a big issue for most educators. How do I evaluate, score, and create interventions for all of my students in all of my classes? It becomes time intensive to do this and to do it well.

In 2014, I discovered that more of my students could meet or exceed expectations after I partnered with Marco Learning. Partnering is the correct term here, as I felt I was bringing in an expert to further expand the effectiveness of my classroom. Student essays were collected and shared with trained online teaching assistants (called Graders) who scored and left feedback on each student’s writing. The individual feedback was encouraging and objective, and it let students know exactly what needed to be improved.

Objective data is the first step in implementing a strong problem-solving framework, and Graders brought that to my students and classroom. Additionally, Graders were able to give more high-quality feedback at a fast rate.

We all know the overwhelmed feeling of lugging home a crate of essays and wondering when the students will get them back. It can take a long time in a busy schedule. Getting this data back faster from my Graders meant I could intervene and spiral at a faster rate.

In this 7-minute video, learn all about how students in Tier II are placed and how they move between tiers.

Tier II: Intensifying Interventions

After receiving Universal Screener results for the grade level and ensuring that teachers are intervening in Tier I classrooms, the data team meets to review qualitative and quantitative data and determine the placement of students into Tier II and III.

Remember that if the instructional model of the school is effective and implemented with fidelity then roughly 8%-10% of students would need Tier II services and roughly 5% would need Tier III services.

With all Tier II, but specifically with writing intervention, it is vital to have a system to maintain all written work. If your school uses 1:1 technology, a digital collection would be ideal, but if not, consider using a small binder for each student. This data is an important way to determine whether a student should exit RtI or transition within RtI.

Some states offer specific forms to use, but if not, it is important to store a cover sheet with the student’s work. This should include daily attendance records, performance or behavior notes, and any scores from their work or progress monitoring assessments.

As a reminder, Tier II progress monitoring should occur about every two weeks at minimum, and students should have a minimum of three data points. This means students should receive Tier II Interventions for a minimum six weeks before a data meeting occurs.

Now that the team has met and rostered Tier II teachers with small groups for their RtI block, what should they be doing to accelerate growth? Most (but not all) schools and districts purchase nationally normed, evidence-based programs.

If the budget allows, these programs provide peer-reviewed articles on the possible outcomes if implemented with fidelity. The third post in this series will provide a list of some of the most used programs. But what if your school doesn’t have access to purchasing a program?

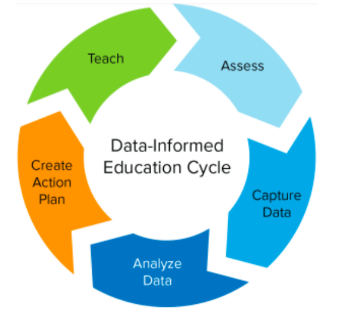

While states differ on the specificity of defining Tier II intervention requirements, there are two main components: 1) a problem-solving approach and 2) evidence-based results from skills or standards intervention. Let’s tackle the problem-solving approach first, which really is just great teaching cycles that teachers do already!

The problem-solving approach drives the educator’s planning and cycle of instruction by intervening at the root of the problem and then reassessing to see if it improved. To read more, take a look at research in School Consultation: Issues in Clinical Child Psychology.

Each week teachers should focus on completing the cycle in the image here. Using data, educators create an action plan for their small group and implement evidence-based strategies. After using teaching best practices, they collect immediate data specific to the standard or skill in focus for the intervention.

The data is collected through standardized progress monitoring tools and then analyzed to either spiral the skills forward or move on to the next need of the students. As a school leader or a teacher leader, creation of planning documents that use this model each week or two would further assist educators in accelerating growth!

Our students cannot wait for trial and error on new or untested interventions. They need interventions that are proven to produce results. After systematizing the problem-solving approach, we turn our attention to evidence-based practices. When purchasing an intervention, it is vital to obtain peer-reviewed results and determine the portability of the results to your students. Some companies tout their results, but upon review, the study and groups involved might not transfer their learning to your student body.

Much research has been done on strategies to include within your Tier II programming, including a ninety-seven page What Works Clearinghouse Educator Guide that provides the examples below:

- SCOPE Editing

- Copy, Cover, Compare Spelling

- STOP, AIM, or PLAN

- Do-What

- Outlining

- SCHEME Goal Planning

- WRITE, DARE, or 3-2-1 for Drafting

- Compare, Diagnose, and Operate

- Peer Revision

- STAR Revising

A separate guide released by What Works Clearinghouse provides the research behind and implementation of the Self-Regulated Strategy Development (SRSD) model. SRSD is a model that moves from teacher modeling and memorization into independent practice. This cycle is one that can be replicated with different modes of writing and has shown to be a significant factor in writing interventions.

We will look further into programs to pilot and strategies to include in the third post of this series!

With a problem-solving approach in place and evidence-based strategies integrated for your interventionist, it becomes important to emphasize standards and skills. For each one week or two week cycle, teachers drill down into the more specific skills within each writing domain. If a parent walks up to an interventionist, a response should go far beyond “We are learning explanatory writing.”

Using specific rubrics and other means of assessment, educators should diagnose student mastery levels at a deeper level. Marco Learning can provide such services to identify specific needs within writing.

Let’s take a look at a seemingly simple standard:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.W.7.2.E-Establish and maintain a formal style

The instinct might be to assess, intervene, and reassess on the level of formal style within explanatory/informative writing; however, intervention that goes deeper will accelerate learning more. Consider the deeper skills embedded in the standard:

- Establish a formal style

- Avoids the use of abbreviations

- Addresses the audience as “the reader” or “one”

- Avoids the use of abbreviations

- Uses third-person pronouns only

- Uses formal words only

- Avoids slang and cliché phrases

- Avoids conveying unknowing or lack of confidence

- Effectively uses syntax and sentence length for academic writing

- Uses objective tone and removes informal, conversational tone

Focusing on formal style alone would be longer than a single week of intervention. Interventionists would use the specific feedback and data within formal style to focus on just 1-2 of the embedded skills each week. The above sequence would then repeat in Tier II until the student closed the gap enough to exit RtI or demonstrated a maintained or widened gap in writing.

In this 10-minute video, learn all about how students in Tier III are placed and how they move between tiers.

Tier III: Individual Interventions

When the Universal Screener indicates that a student is significantly behind or when the student is unresponsive to Tier II interventions, students enter into Tier III services.

Tier III are the most intensive interventions provided by a school outside of special education; therefore, they need to build upon foundational skills. Students in Tier III are not working on standards or the different elements within a standard but rather transferable skills across all elements of writing.

This both ensures rapid growth and readiness to enter Tier II interventions and gathers evidence for or against an IEP.

Before we review some of the transferable skills that are necessary to cover, it’s important to note that the vast majority of schools require a purchased program. This assures results and accelerated growth of those students as well as the collection of proper data to support recommendation for an IEP if needed. This is in line with another requirement for Tier III educators: extensive training and development. The teacher leading the intervention must receive additional training specific to the RtI group.

While there are variations in foundational skills among Tier III programs, many align with research utilized for Written Expression in special education programming. Intervention Central, a leading provider of guidelines and resources for RtI and special education, lists the three main areas:

- Total Written Words

- How many words does the student write in a given time compared to the number of words most students in the grade level write in the same time?

- Correctly Spelled Words

- How many words does the student spell correctly in a timed written response compared to the number of words most students spell correctly in a similar timed-writing?

- Correct Writing Sequences

- How many correct writing sequences does the student have in a timed-written response compared to the number of writing sequences most students have in a similar timed-writing?

- 1 correct writing sequence is scored when two adjacent units of writing are correct in all forms (capitalization, punctuation, etc.)

Other programs focus on different skills or the next level of transferable skills, such as in the Iowa Language Arts Battery Assessment:

- Planning & Organization

- Order of Ideas; Relevance of Ideas; Logic & Coherence; Research

- Sentence Structure

- Complete Sentences; Combining Sentences; Coordination/Subordination; Parallel Constructions; Modifier Placement

- Usage & Grammar

- Pronouns/Plural Nouns; Modifiers; Verb Forms & Agreements; Commonly Confused Words

- Appropriate Expression

- Conciseness

- Unambiguous References

- Word Choice

- Correct Written Language

Most likely, the programs you already use (and any programs you look at purchasing) already combine elements from both of the lists above. Resources and district readiness might mean you are without a structured, prescriptive program for your Tier III interventions.

In that case, simplify the process as much as possible, and review the ideas presented above. Identify the program and sequence of skills to use in all tiers from published research. You can also check out post three in this series for programs to recommend to your administrations and lists of evidence-based strategies to consider!

Continuing the same problem-solving and assessment cycle above, the educator should use the data available to determine the specific needs of the students in the group. The teacher should implement resources aligned with the original data, for instance Total Words Written. The goal would be to increase the amount of words the student can write fluently. The research-based strategies and resources are implemented in a 1:1 or 1:2 ratio.

Extensive modeling is explicit, procedural, and clear for all students. Formative data is collected as students progress with knowledge and skills at each phase of instruction.

Students then work with partners to practice before transitioning to independent practice. Data can be collected in a post-cycle assessment specific to the skill, such as Total Words Written, and then compared with the original data point. Growth or decline is then plotted onto the progress monitoring graph, as seen in the post one of this series.

Most likely, students in Tier III will not all be on the same topic at the same time. Some students will need to stay on a previous topic for additional practice before showing mastery on an assessment.

If there are prescribed sequences to the program, that means one student might be on the first lesson while another is on lesson three and yet another on lesson four. We will focus more deeply on balancing multiple groups in the third post.

Wrapping up our Writing Tiers

Acceleration of our most at-risk learners requires great educators.

Implementing a purchased program or researched practices requires teachers to differentiate for numerous students on an individual level, make authentic relationships, and develop a culture that embraces challenges and growth.

Successes do not come from the purchased tests and programs alone. Teachers create the conditions for students to inventory their strengths and weaknesses and tackle the academic struggle required to close their personal achievement gap. Despite the focus on programs, research, and data, it is the adult in the room who creates the love of growth and learning in our children.

Writing too often gets left untouched in the complicated issues relating to the Achievement Gap. However, it can be key to shifting student outcomes across an entire school.

The research is clear that great writers become great readers and vice versa. Recent research has even looked at the power of writing in creating great mathematicians, historians, and scientists. Great writers become great citizens. Being able to formulate ideas, communicate ideas effectively, and respond to feedback are universal skills for our students.

As an educator, I too have looked at student writing and been worried that our students don’t have the writing skills that their futures require. To move forward with your students, take a deep breath, embrace the RtI approach for writing acceleration, and most importantly, band together with solutions-oriented educators.

Together we can solve the gaps our students face in the education system.

What’s Next

In Part 3 of this series, we will discuss potential problems, solutions, and lists of programs to consider for your Writing RtI program. Please share questions, concerns, or issues you are facing with Writing RtI so they can be addressed in the third post as well! Use the form below to include major questions or perceived problems to implementing a highly-effective Writing RtI.

Brenton DeFlitch, M.Ed & EdS served as a Regional Content Coach for Secondary Education Literacy Interventions in Middle Tennessee. Throughout his 13 year career, he has designed school systems and structures for Reading and Writing RtI in both Tennessee and Pennsylvania. As a previous school leader, he oversaw RtI implementation in middle and high schools, conducted fidelity checks, and trained fellow leaders in running intervention systems.

Help

Help