by Emily Glankler

After a string of broad, metaphorical units about Global Tapestries and Transoceanic Interconnections, the College Board gets uncharacteristically specific in Unit 5 of the AP World History: Modern curriculum. This begs the question: Is Unit 5 really just about revolutions?

Why is Unit 5 called “Revolutions?”

In the simplest sense, AP World Unit 5 is about two different types of revolutions: political revolutions inspired by new Enlightenment ideas and the economic changes sparked by the Industrial Revolution. But industrialization, of course, is far more complex than a simple “revolution.” Most of the unit is more broadly concerned with global transformations that occurred under the umbrella of industrialization: the “Revolution” itself that began in England, but also the constant back-and-forth between rapidly industrializing nations and the parts of the world they are attempting to bring into their economic sphere of influence.

The short answer: the first half of Unit 5 is about the traditional “Modern” revolutions but by 5.6 we begin to go off the rails (train pun very much intended.)

How should we approach the content of Unit 5?

For many teachers, Unit 5 comes right around the end of the fall semester. Many teachers have to make a choice: Do I speed through to try to get all of Unit 5 done before winter break? Do I really want to begin a new era (1750-1900) in the post-Thanksgiving haze only to have it pause for two weeks of winter break? Or should I just slow down on Units 3-4 and start the new era in the new year? All are valid options.

For what it’s worth, I think that Unit 5 very easily lends itself to being split up across winter break. In many ways, the political revolutions (addressed in Topics 5.1 and 5.2) can be extracted from the overall unit and taught on their own. For example, I try to get through Unit 4 by Thanksgiving break so that I can focus on the Enlightenment and Atlantic Revolutions in the awkward weeks between holidays. The Enlightenment actually begins in the previous era anyway and students don’t struggle too much with the overall chronology distinguishing the Age of Discovery (Unit 4) with the Era of Revolutions because, especially if you’re teaching the United States, students understand that the Americas have to be “discovered” before they can declare their independence.

In my mind, Topics 5.1 and 5.2 can stand on their own and either be added on as an “epilogue” to Unit 4 (for those of us trying to squeeze in some more content in the fall semester.) Some teachers get through all of Unit 5 by the end of the semester and that’s a great option too. But I often find that, ironically, splitting the second half of Unit 5 with Unit 6 causes more confusion than breaking Unit 5 apart.

Here’s what my schedule typically looks like:

First Day of School – Thanksgiving: Units 1-4

Thanksgiving – Winter Break: Unit 5A (5.1-5.2)

January: Unit 5B (5.3-5.10)

What details do students need to know about the Enlightenment and political revolutions?

Unit 5 is a trap. Students, and long-time world history teachers, often fall into the rabbit hole during the first half of the unit. Because of this, it’s another unit that benefits from a close reading of the Course and Exam Description.

For example, you might be surprised to look at the CED and realize that not a single Enlightenment philosopher is mentioned by name as a Learning Objective or Historical Development (four female philosophers are offered as Illustrative Examples but otherwise, there’s not a John Locke or Thomas Hobbes insight.) This is a good reminder that the College Board has been increasingly extricating any content that is almost entirely European for, well, AP European History. Do I still talk about Locke/Hobbes/Montesquieu/Voltaire/Rousseau in my class? Sure. But I do it quickly.

Similarly, Unit 5 is far more concerned with thematic causes and outcomes (most notably, growing nationalism) of revolutions around the world than it is worried about kids being able to describe, in detail, the various stages of the French Revolution. Again, the French Revolution (and Napoleon Bonaparte) are almost entirely relegated to the AP European History course. And while it’s tempting to spend days on the US American Revolution from a global perspective, our students’ attentions should be turned more toward nationalist movements and revolutions outside the North Atlantic.

Notice that 5.2 is one of the first topics of the entire course that does include somewhat of a laundry list of specific names and documents that must be covered (for example, “the American Declaration of Independence during the American Revolution, the French “Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen” during the French Revolution, and Bolívar’s “Letter from Jamaica” on the eve of the Latin American revolutions.”) And there’s an even longer list of “Calls for National Unification or Liberation” off to the side that teachers should make sure to introduce to students. This is why I like separating Unit 5 into Part A (5.1-5.2) and then Part B. We can slow down and take the time between Thanksgiving and Winter Breaks to dive into some of the aforementioned documents and movements without rushing onto the cotton gin before midterms.

Why are there so many topics on industrialization?

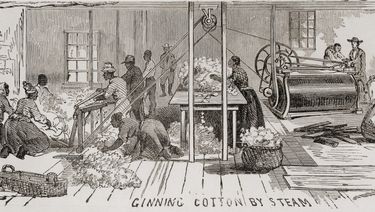

The short answer is that industrialization is the most important development that students need to understand to set up the entire second half of this course. The (slightly) longer answer is that industrialization extends far beyond the canals of England and we need a lot of time to understand how it crept across the globe, involving every region (albeit in different ways.) Because of this, be careful about spending too much time in industrial England and its spread around the “western world.” (5.3 and 5.4) Students need to understand why it started in England (essentially, coal and protection of private property) and why it first moved to Germany, Belgium and the U.S. (new, young countries looking to “catch up” that already had some political or cultural connection to England.) But beyond that, move out of the U.S. and Western Europe as quickly as possible.

One part of Unit 5 that has proven especially confusing for some teachers is determining when to talk about the traditional empires of China, Japan, Russia, and the Ottoman Empire. These are all important states whose responses to the growing power of Western Europe are critical information for students. But their responses to industrialization, like much of Asia, are also linked to imperialism (the main topic of Unit 6.) I have found that going in depth in Unit 5 is helpful: the Opium Wars, Meiji Restoration, Ottoman Enlightened reforms, and Russian economic woes are all really important for understanding the impact of Western ideas. Then, you can always just “check back in” on them towards the end of Unit 6 to remind us what each state’s status is by the turn of the 20th century.

I still don’t quite understand “Revolutions.” What other resources are out there to help me get through Unit 5?

Here are some of my other favorite tried-and-true resources for Unit 5.

YouTube Reviews

- “AP World History Unit 5: Revolutions” (Anti-Social Studies)

- “AP World History Unit 5 Playlist” (Heimler’s History)

- “AP World History Modern: Unit 5 Review” (Stephanie Gorges)

- “Illustrative Examples: Declaration of the Rights of Woman” (Freeman-pedia)

Unit 5 Lesson Plans and Resources

- Unit 3 LEQ Workshop / “Build Your Own Ear”Indigenous Res”Enlightenment Speed Dating” lesson available in the AP World Teacher Starter Pack (Anti-Social Studies)

- Unit 5: Revolutions (Freeman-pedia)

Emily Glankler has taught almost every Social Studies course for the past decade from 6th grade World Cultures through AP® U.S. History but her favorite course to teach is AP® World History. She has taught AP® History courses at both private and public high schools in Austin, Texas and she was the team lead responsible for bringing AP® World (and building the curriculum from scratch) to the last two high schools where she has taught. Emily has also led professional development within Austin ISD as an Instructional Coach as well as presenting to an audience at SXSW EDU about incorporating current events into the core curriculum. She has a B.A. in History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and an M.A. in History from Texas State University. In addition to teaching full time, Emily also writes and produces a history podcast called Anti-Social Studies that is used by teachers and students in history classrooms around the country.

Help

Help