by Emily Glankler

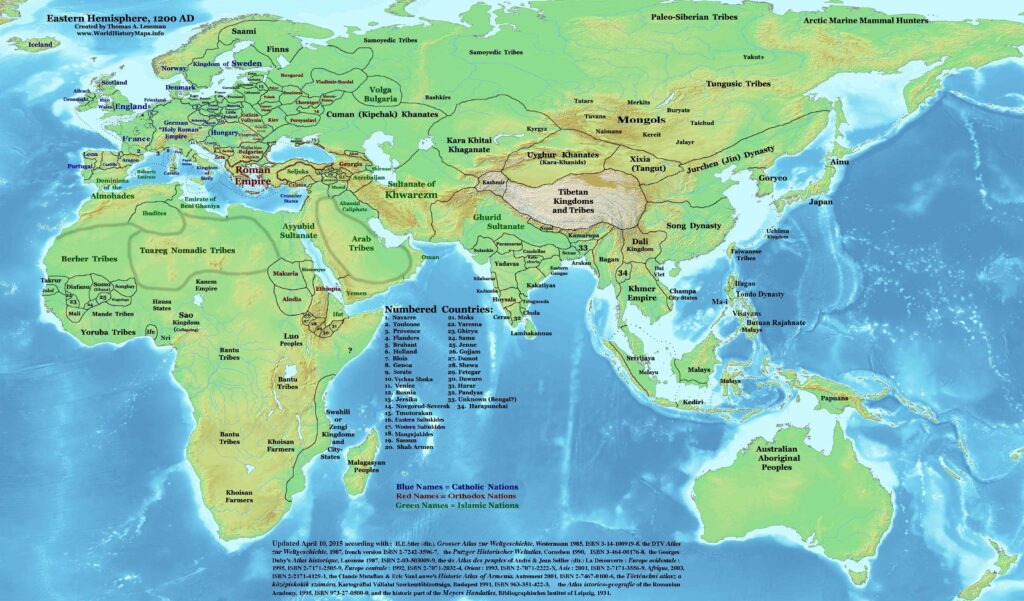

In 2018 the College Board shook the AP World History universe to its core by announcing that the course would no longer start in 8000 BCE. No more Neolithic Revolution, Egyptian Pharaohs, or Alexander the Great. No more comparing Han China with the Roman Empire (an old standby for those of us “Old Timers.”) Nope. From now on, AP World History would begin in the year… 1200?

This news was confusing to many experienced World History teachers because 1200 C.E. is smack dab in the middle of the Postclassical Era (600 – 1450 C.E.)

Why does AP World History: Modern start in 1200 C.E.?

First, for some context (see what I did there?), we should note that the College Board originally set the course to begin in 1450 C.E. This prompted “outcry” from teachers as this would essentially cut out the entire Golden Age of non-western civilizations. Students would now think the history of the world “began” right at the moment of Europe’s “Age of Discovery,” erasing long lasting pre-colonial civilizations in America, Africa, and Asia. To compromise, they pushed the course back by 250 years and now we begin in the year 1200.

The best explanation I give my own students as to why we jump into history mid-era is simply that we need to gain context of the way things were before we can discuss how things change. While many people reasonably set the biggest shift at 1492 with the connection of the eastern and western hemispheres, an earlier shift is actually the key focus of Units 1 and 2: the Pax Mongolica. Any guesses as to when Genghis Khan unified the various nomadic tribes of the Mongolian plateau and began his era of conquest and transformation? 1206.

Just like AP US History technically starts in 1491 – so that students can get a glimpse of North American life before Columbus shakes everything up – in AP World History our students need to get a vague idea of what the world was like before everything changed. We need to study the great civilizations of Asia and Africa just on the eve of their conquest. In other words, students need to see the broad “Global Tapestry” before Genghis Khan (and then, Western Europe) tears it apart to make something new.

With this interpretation, how should we approach the content of Unit 1?

Essentially, Unit 1 is our contextualization for the rest of the course. The College Board sends us on a region-hopping adventure to check in with one or two key civilizations in each part of the world so that we have a baseline to compare from in future eras. Although Unit 1 keeps us mostly in Afro-Eurasia, this approach is even more clear in the Americas. In Units 1 and 2 we need to establish what was going on in the Americas before Europeans arrived in the next era. For those of us who remember analogies, Columbus : Americas :: Genghis Khan : Eurasia.

I think of the entire course as one giant LEQ answering the prompt:

Evaluate the extent to which modern World History has been defined by competition between the “East” and the “West.”

For more on this idea, you can read my article here.

Does chronology even matter in Unit 1?

The only chronology for Eurasia that matters in Unit 1 (and 2 for that matter) is Before the Mongols and After the Mongols. For example, students would need to understand that the Song Dynasty ruled China before the Mongol invasion and the Ming Dynasty restores Chinese rule after the Mongol century. But beyond that, students can zoom out and look at the big picture of each civilization without stressing over the order of its rulers, conflicts, or other traditional chronology.

Instead, I recommend approaching Unit 1 thematically. This is a great opportunity to introduce and cement the SPICE-T themes into our course. Can students discuss the social structures of Song China? (A Confucian society with some social mobility thanks to the civil service exam system.) Can students identify political and cultural elements of East African civilizations that make it unique from other parts of the continent? (Small trading city-states that are heavily influenced by Muslim traders, evidenced by the language of Swahili and the establishment of Islamic governments in some cities.)

With my own students, I simplify the “Global Tapestry” down to two essential questions:

- How did key states gain and maintain power in the region?

- How did they promote unity and stability within their state?

If it’s all just context, should we just combine Units 1 and 2 together?

Short answer: sure!

Unit 1 focuses on the states from 1200 to 1450 while Unit 2 explores the networks of exchange and interactions within that same era. For example, students learn about the states under Dar al-Islam in Unit 1 and then go back and look at the spread of Islam as part of cultural diffusion in Unit 2. This can be confusing for students who assume that when we move from one unit to the next we are also moving forward chronologically.

Because of this, many teachers, myself included, combine Units 1 and 2 in some way. In my classroom, I don’t have a big unit exam until we are through Unit 2 (I had a smaller test “check in” after Unit 1 to make sure we were on track.) Depending on your textbook, you could just weave the topics of Unit 2 into your teaching of Unit 1. (For example, after you teach 1.1 East Asia and 1.2 Dar al-Islam, shift over and look at the Silk Road (2.1), etc.) Personally, this seems unnecessary as long as you are very clear with students that all of the content from Units 1-2 is within the same years of 1200 to 1450. This is also a good practice for future eras that are also divided into two units (Units 3-4: 1450-1750 C.E.; Units 5-6: 1750-1900 C.E.)

I still don’t quite understand “The Global Tapestry.” What other resources are out there to help me get through Unit 1?

You are not alone. Many experienced teachers have a hard time just diving in mid-era and making sense of “The Global Tapestry.” Here are some of my favorite tried-and-true resources for Unit 1.

YouTube Reviews

- “WHAP Unit 1: The Global Tapestry” (Anti-Social Studies)

- “AP World History Unit 1 Playlist” (Heimler’s History)

- “AP World History Modern: Unit 1 Review” (Stephanie Gorges)

Unit 1 Lesson Plans and Resources

- SPICE-T Comparison Chart for Unit 1 Review (Anti-Social Studies)

- Statebuilding and Innovation from 1200-1450 (Marco Learning)

- The Mongol Empire (Marco Learning)

- Files: Lesson Plan, Teacher Commentary, Student Handout, Homework

- The Global Tapestry (Freeman-Pedia)

Emily Glankler has taught almost every Social Studies course for the past decade from 6th grade World Cultures through AP® U.S. History but her favorite course to teach is AP® World History. She has taught AP® History courses at both private and public high schools in Austin, Texas and she was the team lead responsible for bringing AP® World (and building the curriculum from scratch) to the last two high schools where she has taught. Emily has also led professional development within Austin ISD as an Instructional Coach as well as presenting to an audience at SXSW EDU about incorporating current events into the core curriculum. She has a B.A. in History from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and an M.A. in History from Texas State University. In addition to teaching full time, Emily also writes and produces a history podcast called Anti-Social Studies that is used by teachers and students in history classrooms around the country.

Help

Help