Writing benchmarks are a powerful tool that can help teachers and administrators better understand, track, and evaluate student writing performance and growth over the course of the school year. This guide is intended to help you understand how to leverage this tool effectively for your school or district.

What are Writing Benchmarks?

Writing benchmarks are periodic assessments that measure student writing skills. They may be called different things at different schools and districts. For our purposes in this guide, when we talk about writing benchmark assessments, we’re talking about the more formal, on-demand writing assessments that schools administer at set points throughout the year (generally once a quarter).

Each benchmark administration tends to focus on one major essay type (e.g., informative, argument, and narrative, the big three as defined by the Common Core, or other types including expository, analytical, or persuasive writing). Read more about essay types here.

These essays may be polished pieces, or more likely, are written on-demand (i.e., timed) during a class period. Essays are evaluated on a rubric that is looking for skill around ideas, evidence, elaboration, organization, and (typically less emphasized) conventions.

Here are some (free) example benchmark prompts from the Vermont Writing Collaborative.

Done well, writing benchmarks should provide instructional value directly to students and teachers, as well as critical data for administrators. If you’re considering implementing (or resurrecting) writing benchmarks at your school, the key to success is upfront planning.

But before we dive into what to do (and what not to do!), let’s start with some basics.

“Students need the opportunity to grow over time. To truly prepare students for the future requires a schoolwide, cross-grade commitment to teaching and assessing writing.”

— Lucy Caulkins

Are Writing Benchmarks Formative or Interim Assessments?

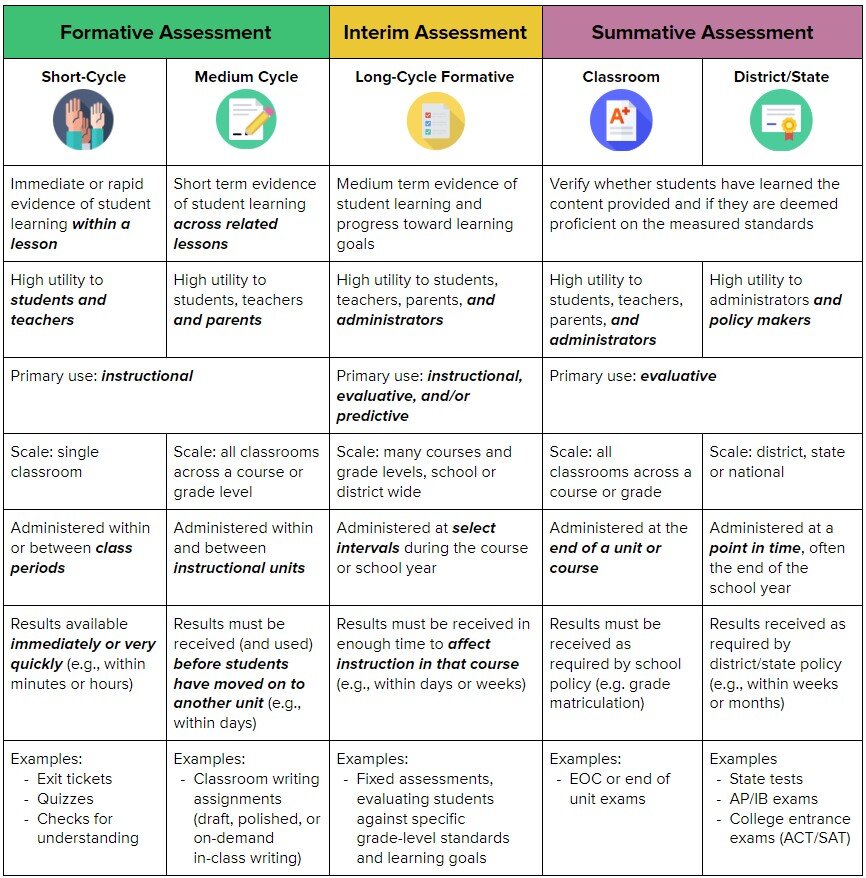

Trick question! Writing benchmarks can be either interim or formative assessments – it all depends on how the results are used. In fact, designed properly, they can be considered both formative AND interim. Interim assessments are sometimes called long-cycle formative assessments.

Whether a benchmark assessment is properly designated as interim or formative is determined primarily by use—who is using the results, how often and under what conditions is it administered, when are results available, and what decisions are made from the data.

Whether formative, interim, or summative, each type plays an important role in a comprehensive assessment system. While there are many levels of stakeholders to consider, the National Panel on the Future of Assessment Practices makes it clear that ALL assessments should serve to improve student learning and to document that learning for a variety of stakeholders.

What’s the difference between formative, interim and summative assessment? Here’s a breakdown of the three assessment types:

District leaders should aim to design effective benchmark systems that capture 1) the value of formative assessment to impact student learning and instruction and 2) the value of interim, aggregate data for progress monitoring towards important goals.

The Critical Importance of Writing Benchmarks

There is a growing demand for students to develop stronger writing skills in their K-12 education. Accordingly, major summative and high-stakes tests require more student-constructed response to better gauge higher-order thinking skills. This is not just coming from academics and employers. In a recent poll, American voters said their top three priorities for public school students are to “Read and write” (84%), “Be good citizens” (76%), and “Stay safe from violence and physical harm” (75%).

As Steve Graham and Dolores Perin point out in their report Writing Next, along with reading comprehension, writing skill is a predictor of academic success and a basic requirement for participation in civic life and in the global economy. Yet every year in the United States large numbers of adolescents graduate from high school unable to write at the basic levels required by colleges or employers.

In addition to not being prepared for college or jobs in the U.S., students are not competitive globally. OECD reports show that U.S. graduates’ literacy skills are lower than those of graduates in most industrialized nations, comparable only to the skills of graduates in Chile, Poland, Portugal, and Slovenia (OECD, 2000).

Data on students’ writing skills helps uncover these gaps and allow educators and students to act to fix them. Further, using writing benchmarks as a performance assessment, rather than relying on multiple choice exams, is the best practice.

“Research has shown that the use of performance assessments which are locally administered and use multiple sources of evidence offer the opportunity to turn assessment systems to serve their primary purpose—assisting students in learning and teachers in teaching for higher order intellectual skills.”

— George Wood, Linda Darling-Hammond, Monty Neill and Pat Roschewski

The briefing paper prepared for members of Congress goes on to say that “the assessment systems of most of the highest-achieving nations in the world are a combination of centralized assessments that use mostly open-ended and essay questions and local assessments given by teachers which are factored into the final examination scores.”

When writing instruction is weak, all parties – educators, students, teachers, and administrators – can feel at a loss to help students succeed on rigorous writing examinations at the end of the year.

“I’ve seen teachers guffaw incredulously at samples of student writing. It is not surprising that people in any school system that has treated writing as a frill, as an extra-credit option, will feel that the standards contained in the Common Core…are inaccessible.”

— Lucy Caulkins

Benefits of Writing Benchmarks

Benchmark assessments deliver important information to teachers on student progress and growth of writing skills. These data snapshots help teachers understand where students are in that moment of time, including areas of strength (what a student is doing well) and areas for growth (where they may need extra support or help).

They also allow teachers to see a student’s trajectory: where each child stands in relation to grade-level learning goals, skills, and standards and how quickly he or she is progressing towards those targets. This information can be equally valuable for other key stakeholders – school leaders, instructional coaches, parents, and, of course, students.

Here are the key benefits of writing benchmarks!

Writing benchmarks:

- ACCELERATE STUDENT LEARNING

Providing students with quantitative data and qualitative feedback on their performance helps to foster self-reflection and goal-setting. It’s a critical component for engaging students as owners and directors of their own learning. Paired with their body of work from classroom assignments, benchmarks complete a portfolio that students can use to demonstrate their work and their growth over time.

In a review of factors influencing student achievement across studies of more than twenty million learners, John Hattie found that the most influential factors are for a learner to 1) have clear, ambitious goals, 2) get feedback that highlights progress toward these goals, and 3) know of next steps that are within reach. This is exactly what writing benchmarks can accomplish.

- PREPARE STUDENTS FOR SUCCESS ON LATER EXAMS

Sometimes writing benchmarks can be used to prepare high school students for specific high-stakes essay exams. In the high school class of 2019, about 1.4 million students took the essay option with the SAT, or 64% of the total number of students tested. For the ACT, over 900,000 students took the ACT with its essay, or 47% of the total number of students tested.

Note: Even for colleges who have dropped the SAT/ACT essay requirement, students must still demonstrate competent writing. Those colleges still want to see a graded essay from a classroom assignment.

While the personal essays in college applications offer value to admissions officers, what these personal essays reveal about writing skill is inconsistent because the advice and support students receive in preparing applications varies widely, as Christoph Guttentag, Duke University’s dean of admissions, points out. Either way, students will need to prepare to prove their writing skills, and writing benchmarks allow them to practice and determine their current level.

- IMPROVE THE QUALITY OF TEACHING

Done well, writing benchmarks should elevate the quality of teaching, as well as elevate the level of student writing. By objectively measuring where students are starting and mapping the development of writing skills over time, educators gain important insights to focus their future lesson plans.

NWEA, a leading K-12 assessment provider, outlines several specific ways educators can use the results from interim assessments like writing benchmarks:

- To target additional resources for students and teachers – examples of this include placement into intervention or talented-gifted programs for students, and professional development opportunities for teachers

- To identify patterns and trends in learning for particular students or groups of students

- HELP PARENTS UNDERSTAND HOW THEIR CHILD IS PERFORMING ACADEMICALLY

For parents, interim data can help them understand how their child is progressing, what areas he or she needs extra help in – and where he or she is doing well.

- EQUIP ADMINISTRATORS WITH TIMELY DATA FOR DECISION MAKING

For principals and district administrators, the objective, standards-aligned data from writing benchmarks are useful for tracking progress toward critical milestones – for example, are our third graders on track to be fluent readers by the end of the year? Such data is also important for evaluating program impact and predicting outcomes for various accountability tests.

Obstacles to Effective Writing Benchmarks

Writing benchmarks must be designed to be valuable and useful for students, the most important stakeholder! In theory, the purpose of assessment includes valuable feedback for students, but in practice, the primary beneficiary of the data about what students have learned and what skills need support is administrators, reducing the benefits to progress monitoring and accountability.

Even in places where teachers also are part of the benchmark analysis process and are given time to determine instructional adjustments and next steps, students often experience benchmarks like a black hole – writing goes in, and very little actionable feedback comes out.

While incredibly valuable, interim assessments can be operationally difficult to execute and prohibitively time-consuming to evaluate. Even if proper planning has occurred, the most thoughtfully designed benchmarks can still fail to produce the intended rewards due to simple – but thorny – operational and logistical issues.

Often, teachers do not have the time or capacity to norm, calibrate, and score these assessments on their own. Or worse, teachers spend days scoring assessments and there is no time for the analysis and action planning that drives student achievement, rendering the scores meaningless. Plus, when students learn there is no consequence to their performance (aka they never see a score or receive feedback), performance suffers and the importance of the assessment is diminished.

Here’s are the most common stumbling blocks to writing benchmarks:

- OPERATIONAL & PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS, OBSTACLES, AND COSTS

- Building testing and reading days into the calendar

- Hiring subs and pulling teachers out of class to grade

- Implementing successful large-scale norming and calibration (across grade levels, and sometimes even campuses)

- Completing all of the grading in a limited number of days (usually 1-2 max)

- STALE DATA

As a result of the above, it’s no surprise that writing benchmarks fail to deliver timely data. The main complaint about so-called “formative” assessments from testing firms is that almost all fail to get results back in time for meaningful instructional adjustments. Thus, these assessment lose the value that lies in formative assessment.

“Because the results come back for topic X when the teacher has already moved on to topic Z, such tests cannot be regarded as formative assessments.”

— W. James Popham is Emeritus Professor in the UCLA Graduate School of Education and Information Studies

- LACK OF TEACHER BUY-IN

As many district leaders can attest, “You say the word ‘benchmark’ and teachers freak out.” Since the prompts for most writing benchmarks come mandated from the district, teachers have less buy-in on the exact task asked of students from the start. Teachers are less excited about and less invested in assignments that aren’t their own.

When these essays add to their grading fatigue, teachers feel frustrated by having to spend a full day grading and missing valuable class and prep time. With many teachers already taking several sick and personal days a year to “catch up” on grading classroom assignments, these added urgent grading days that cost them direct instructional time with students can lead to severe teacher resentment.

Irrelevant or outdated content in the writing benchmarks can add insult to injury for teachers, since it doesn’t align to their curricular objectives. Keep in mind that district writing benchmarks require reviewing and updating.

“These [district writing] benchmarks (and the posters upon which they most commonly viewed) are not regularly referenced by instructors, nor are they designed in a manner that students could easily comprehend”

— Sharon Public Schools, ELA Program Review 2010

- TIME CONSTRAINTS & MISALLOCATION OF RESOURCES

It takes so long to norm and score all of the essays that there is little to no time left for teachers to actually use the data; teachers miss out on data analysis, instructional planning, goal setting, professional learning and collaboration, etc. These are critical parts of the assessment loop, and missing them causes a breakdown in the cycle.

- NO FEEDBACK FOR STUDENTS

And of course, most benchmark processes allow no time for feedback. Students take benchmarks less seriously when they don’t receive feedback; the process is failing to respond to a key stakeholder (the learner). As assessment expert Rick Wormeli points out, if there is no feedback, the assessment or task does not have much instructional value compared to when there’s feedback.

“Every September in my school district the School Wide Write – a seemingly innocuous benchmark assessment for writing – can cause stress, confusion, and even anger for many middle school teachers and students. This apprehension is not surprising given that assessment itself often remains ‘mysterious to both teacher and student.’”

— Annemarie Mai, A Critique of the ‘School Wide Write’ within Effective Writing Instruction and Assessment

Designing A Better Writing Benchmark Cycle

Formative assessment is a powerful tool to help ALL stakeholders better understand, track, and fuel student preparedness, performance, and growth. To be most effective, formative assessment must be ongoing, consistent, and designed in conjunction with thoughtful and complete feedback and data cycles. This is no small task – it requires upfront planning, coordination, key teacher and student supports, and of course, feedback.

When it comes to formative assessment of writing, the stakes get even higher. One of our chief focuses at Marco Learning is to partner with districts and schools to think rigorously about what formative assessment of writing should look like in classrooms district-wide to best prepare students for success.

Now more than ever, writing is a foundation skill. It’s not just tested on end-of-course and Advanced Placement exams but also college essays, almost every college course, job applications, and on-the-job requirements. We want students to be writing confidently and thinking critically in every situation.

To do so, educators need to return to the basic principles of learning: practice and feedback. Learning how to write is just like learning any other skill. The more opportunities a student gets to write and the more feedback they receive on their writing, the more they’ll advance in this skill.

If you want to implement a well-functioning assessment cycle that measures higher-order skills, such as writing, here are all the key steps:

Writing Assessment Roadmap

- SET THE VISION

Districts need holistic strategy when it comes to writing instruction and assessment. In order for the stakeholders in your school or district to reach a shared understanding of where the school is and where it should go in the future, you need to have a vision. The authors of How to Help Your School Thrive explain that an ideal vision is one that “all staff members recognize as a common direction of growth, something that inspires them to be better” and one that “announces to parents and students where you are headed and why they should take the trip with you.”

For Dr. Ebony Lee of Clayton County Public Schools (CCPS), creating a vision meant first asking, “What is the profile of a graduate that we are wanting?” and comparing that to the current reality. This helped her district realize that they wanted greater access, and so they committed to higher performance. When evaluating the strength of your vision, Dr. Lee suggests, “Ask yourself, How present and alive is your vision? Can an individual classroom teacher or parent repeat the core tenants?”

“How present and alive is your vision? Can an individual classroom teacher or parent repeat the core tenants?”

— Dr. Ebony Lee, Clayton County Public Schools

Award-winning school administrator Leo Corriveau warns that developing a school vision isn’t always easy: “it takes courage to be a leader today.” His district “outlawed killer phrases such as ‘We can’t do it’ or ‘There’s no money’” and had to rethink staffing and reconsider the entire school calendar in the process of creating a new school vision. He says, “Everything has to be geared toward what you are trying to achieve, which is student learning.”

When you’re developing a new school vision, it’s wise to expect resistance and obstacles. Staff members might have some (or all) of the following thoughts at first:

- What is the need for a new vision?

- Will I be able to live with the new vision?

- Will I be able to support the new vision?

- What will the new vision expect of me?

- How will my world change as a result?

- Will I be able to continue doing what I’ve always done? Why or why not?

- Do I believe in this new vision?

- Do I believe in my school’s ability to achieve this vision?

- Do I believe I can help make the vision happen?

To alleviate some of your staff members’ concerns and strengthen your vision for the school, you can also involve staff members in developing the vision. Consider asking staff members to discuss the following questions in groups:

- What evidence can you think of that we are meeting our current vision?

- What kind of school do we hope to be?

- What do you think should be reflected in our vision statement?

- What do we need to do differently to achieve this vision?

- How are we different from other schools?

After you have created a clear vision for your school, your strategic plan for achieving it needs to be very focused. Dr. Lee of CCPS says, “We went from having many performance objectives to only four that directly align to our Strategic Goals.”

The major advantage to having fewer initiatives is that you can channel resources and energy into each one and fully support it. For CCPS, this support meant “strengthening partnership with NMSI, College Board, Marco Learning, specialized support staff at our district and other stakeholders, all to reinforce our core focus areas.”

- OVER COMMUNICATE

Simply having a vision for writing and assessment in your district is not enough. You need to make sure the vision is communicated often and consistently to all audiences.

Conventional wisdom from marketing is that people need to hear a message at least seven times before acting, aka The Rule of Seven. A study by Microsoft showed it takes up to 20 times! When you consider the sheer volume of communication already bombarding your staff and teachers (nearly a million words a month), issuing an occasional memo or giving a series of speeches makes only a tiny impact.

As Education Week’s special report points out, teachers can be a performance assessment’s “biggest boosters or its toughest foes.” Thus, it is especially critical to keep teachers well informed about the assessment program, its pedagogical purpose, and its connection to the larger vision.

In addition to this explicit communication of your vision to teachers, your communication plan should include implicit communication—what your behavior says about your vision. The behavior of your entire district or school leadership team should reflect that vision, and you should be cognizant of any seeming inconsistencies (and be ready to address and explain them). If your behavior reflects your vision, you will gain credibility. If your behavior undermines your vision, you’ll lose credibility, no matter how well you communicate your vision through words.

“Clear communication across all stakeholders of our high expectations for students was our biggest thing. We adopted the motto, “We are committed to high performance” and we told every stakeholder this as often as we could.”

— Dr. Ebony Lee, Clayton County Public Schools

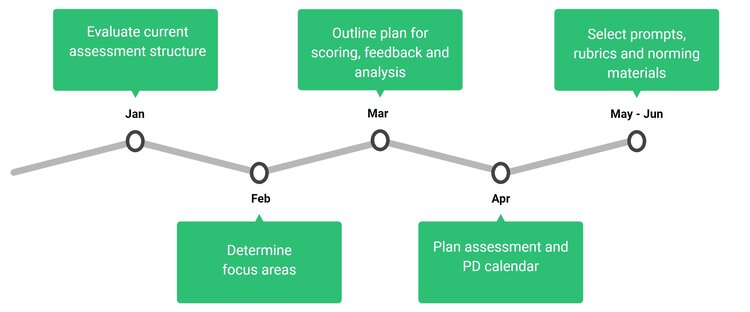

- PLAN, PLAN, PLAN

Proper planning is crucial to kicking off a successful writing assessment cycle. Some key components to plan (and a sample seven-month planning horizon) include:

- Evaluate current assessment structure. Start by identifying committee members to help evaluate current assessment practices and plan the assessment cycle. These individuals not only help in the initial planning but also serve as experts within their schools or departments during the initial implementation.

- Narrow down and determine the focus areas for your assessments. Which courses? Which grade levels? Which types of writing? Be sure to begin with the end in mind and plan backwards from any important assessments. Thanks to their performance nature, writing benchmarks are much simpler than “blueprinting” for traditional assessment. You should still use backwards mapping to determine which writing types students will learn by which dates and how much time they will have in class to write their assessment responses.

- Outline your plan for scoring, analyzing, and giving feedback on the assessments. How will you train and carve out time for your own teachers to evaluate the student writing? Will you use a third party service like Marco Learning? Either way, as Rick Wormeli points out, “If there is no feedback, it turns out… the assignments don’t have much instructional value compared to when there’s feedback.”

“So in the same planning breath as I design my assessment, I’m going to design how will students get feedback on this and how will it inform my lessons.

— Rick Wormeli

- Plan the assessment and PD calendar. One major tactical question district and school leaders must answer is “how do you align your PD calendar with your formative assessment calendar?” If you are collecting data, you must carve out time for formal quarterly PLC or department meetings to look at that data and determine instructional changes. Furthermore, your assessment and PD calendars must be aligned so that teachers have the opportunity to analyze relevant data and receive instructional support in a timely fashion.

Sample Assessment & PD Calendar

© Marco Learning 2020

Remember, carving out common time for teachers to meet and discuss student writing is worth it!

“My colleagues and I have been dazzled by the results when teachers are given opportunities to pore over their collective students’ writing. As you do so, you can clarify shared goals for writers, norm expectations across grade levels, and, ultimately, become more expert at providing students with the individualized feedback they need for success.”

— Lucy Caulkins

- Finally, select the specific assessment materials that your staff will use: prompts, rubrics, and anchor papers . Rubrics (i.e., how student writing will be evaluated) can be intimidating, but they don’t need to be. The goal is simple, well-described, commonly-used rubrics that are aligned to your academic standards. If you don’t already have these valuable assets in place (many don’t), you’ll need to gather them for your instructional leaders and teachers. Here’s a quick-start guide and a full list of resources in our Ultimate Guide to Rubrics.

- TEACHER TRAINING

When it comes to training teachers for writing benchmarks, here are some valuable topics to cover:

- Clarify the learning goals. Review the essay type that will be used in the benchmark, its purpose, and the common rubrics that will be used to evaluate student writing.

- Norm on expectations. This can be a challenging and time-intensive process, but it is absolutely worth the effort. Norming and calibrating teachers ensures that data is objective, reliable, and actionable. We recommend using an inquiry framework and providing lots of student work samples so your team can benefit from hands-on experience and authentic training.

- Discuss student buy-in. To be most successful, students need to have a clear understanding of goals and expectations, how they’re performing today relative to these benchmarks, and what they need to do to improve. Teachers should be prepared to review the rubric with students. We recommend using student-friendly language in your rubrics and removing negative framing – the goal is for students to see what they can do, not what they can’t. When students can read and use rubrics with confidence, they’ll be more engaged and able to take ownership over their learning and goals. This practice also helps build a common language for writing among teachers and students.

- Prime students for feedback. If you’re planning to respond to students with feedback on their writing benchmarks (we hope so!), you’ll want to familiarize students with the process of receiving feedback in advance. Priming introduces predictability and structure, reduces anxiety, and increases student buy-in and success. Read about some specific ways to do that here.

- Recap prior benchmark results. If prior writing benchmarks were administered and scored, teachers can review the scores and holistic class feedback to get a sense of how students have performed previously.

- Provide students with guidance on the prompt and response. This may include unpacking the questions as a class before beginning the assignments, or possibly providing guiding questions to help students understand how to unpack the question and develop a response themselves.

- ADMINISTER THE ASSESSMENTS

When the big day finally arrives, keep these two best practices in mind.

First, the way in which an assessment is administered to students matters. The logistical details need to be consistent! This makes the assessment’s results as objective as possible so that they can be considered valid and meaningful. You don’t want changing external factors to cast doubt on how comparable the academic performance insights are.

As Pearson’s report on Administration Practices for Standardized Assessments explains, “Standardization attempts to control these external factors to the greatest degree possible so that the assessment is a valid measurement tool that produces meaningful results.”

Here are some factors you’ll want to control for:

- Time limits

- Make-up policy

- Materials students can use (e.g., scratch paper or internet access)

- Directions for administering the assessment

- Accommodations or modifications for students with disabilities or English language learners

Second, take precautions to promote academic integrity. Since studies find that more than 1 in 10 students cheat, it’s best to assume that without intentional efforts to prevent cheating, it will occur. In addition promoting consistency among teachers and administrators regarding academic integrity expectations and being prepared to reinforce the code of conduct, the following assessment administration practices will help create a culture of academic integrity:

- Schedule enough time.

- Prep technology and materials.

- Have a technology backup plan.

- Schedule benchmarks on high attendance days and/or encourage attendance.

- Assign proctors and remind them to be vigilant.

- Immediately collect (or have students ‘submit”) their essay.

- SCORE ASSESSMENTS AND GIVE FEEDBACK

Your students analyzed texts and wrote thousands of responses. Now what?

Those writing samples need to be scored and given feedback, and quickly. All too often, people make the mistake of focusing exclusively on the scoring and forget about providing feedback on the writing. But that reduces writing to a number and a score by itself has little learning value.

Remember, students are always the #1 constituent. Plus, the work of assigning a score goes hand-in-hand with the act of crafting actionable feedback for the student on their particular piece of writing being assessed.

Districts who are experienced with writing benchmarks use rigorous techniques such as blind scoring, back scoring, and double scoring, all of which take time. At a minimum, you’ll want to follow these steps if you’re having your own teachers and staff do the scoring:

- Review the learning goals and expectations defined in the writing prompt and rubric

- Study the distinctions between point values on the rubric

- Calibrate on anchor papers for each point value and rubric component

- Score a sample

- Resolve discrepancies

- Review the 7 Hallmarks of Effective Feedback

- Mix up assessments so no one is scoring their own students

- Periodically monitor scores and score distributions.

That is where Marco Learning comes in!

Marco Learning support ensures all stakeholders can get objective and actionable data quickly—without the operational challenges that normally come with performance assessments. School or district administrators can upload rubrics, prompts, and other supporting documents such as anchor papers and exemplars. With a few clicks, teachers share their writing benchmark assignment and upload their students’ work. Just a few days later, teachers receive normed, detailed, and personalized feedback and data reports for their classes.

“We knew we wanted to arm teachers with better data about student learning and directly benefit students through timely feedback on formative assessment. These cycles of practice and feedback are critical to student learning and growth, and we wanted to foster and prioritize this without overwhelming our teachers.”

— Kristie Heath, Clayton County Public Schools

- USE THE RESULTS TO DRIVE INSTRUCTION

If the downfall of multiple-choice tests is that they encourage teachers to focus on low-level, easily measured skills, the inverse should be true, too: “Give students rich assessment tasks worth teaching to and help support educators to redesign their instruction to boost development of skills like analysis and inference.”

In fact, studies on state performance assessment programs (performance assessment means students are constructing, most often writing, their responses) found that teachers had higher expectations for student learning, and principals had higher expectations of what teachers could do.

Here’s how we recommend making the most of your writing benchmark program to drive instruction:

Administrators. For each benchmark administration (two to four times per year), administrators should meet to analyze the results. You should review the aggregated scores and feedback across all students. Results can be analyzed by grade level, school building, teacher, and class period, and you can drill down into individual class periods and student reports to see qualitative feedback for insights into the score drivers. We also recommend scheduling mid-year and end-of-year reflection meetings to gather key stakeholders (such as the initial committee members) and reflect on methods for continuous improvement.

Teachers. The Marco Learning Teacher Report provides a quick but detailed snapshot of each class period’s performance and includes their grader’s thoughts and feedback. Data on this report includes:

- Holistic trends and insights

- Top and bottom performers

- Granular performance data by rubric component and FRQ type

These reports can be used to:

- Identify student performance trends in the qualitative and quantitative data (ideally with their instructional support staff)

- Group students based on targeted need for small group exercises

- Inform class-wide discussions, using select student work as exemplars

It’s important to note that when it comes to assessments, like benchmarks, teachers often perceive these as having little direct impact on their classrooms. They also see time as a barrier. Many district leaders agree that a major part of assessment is teacher buy-in so it’s effective in the classroom. To that end, teachers need to know that assessments are not about compliance but are a critical part of the teaching and learning process.

“When I talk to our teachers, they are so excited to be able to have an idea of what they needed to go back to focus on. They had different ways of utilizing formative data: posting class summary data for the class to talk about skills broadly, to using the individual feedback reports for one-on-one student conferencing.”

— Kristie Heath, Clayton County Public Schools

Instructional coaches. They look at the data alongside teachers, and based on trends, support them in creating informed action plans with targeted extensions and interventions for students. Instructional coaches are also there to help make sure teachers are considering multiple sources of data on student learning, and not relying on just one form of formative assessment.

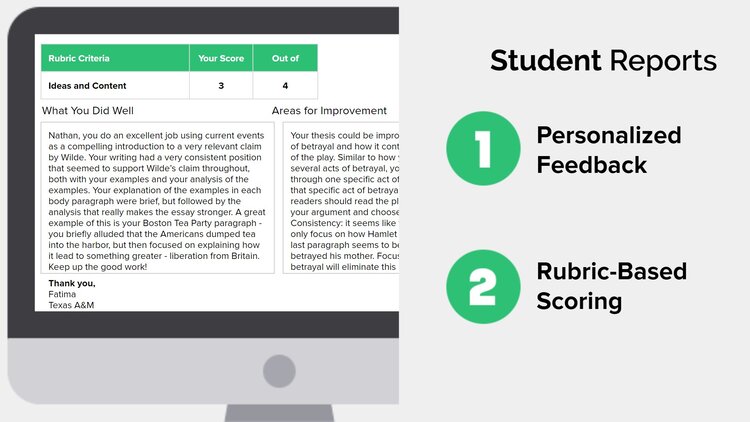

Students. In Marco Learning’s model of writing assessment, each student also receives their own individual student report. The reports are specific for every student, and each report includes feedback on the student’s areas of strength and areas for growth.

These student reports can be printed and passed back, or they can be passed back digitally via Google Classroom or email. Students can then write on them, take notes, set goals, and use the reports to guide their studying.

Student reports are a great tool for:

- Student reflection, goal setting, and revision

- Student-teacher conferencing

- Peer or small group activities

Conclusion

Writing benchmarks are meant to function as long-cycle formative assessments. This way, they give teachers and students both timely and substantive data to understand where they are, identify gaps in learning, and create action plans in response. Thus, adopting assessment practices that produce learning value for ALL stakeholders is critical.

Administrators often know that timely, useful data helps them determine where students are so that they can positively impact teaching and learning, which is ultimately everyone’s shared goal. The power of writing benchmarks to advance critical skills and provide information that can make a difference in an entire community’s learning trajectory cannot be overlooked.

Ready to get started?

If your district or school is already heading into the planning process, get in touch with our feedback experts – we’d be happy to help.

Help

Help